rotavirus particle

I have for some time taught my third year students about how one must weigh relative risk vs. relative benefit when it comes to vaccination – with the Wyeth live rotavirus vaccine that was withdrawn in 2000 or so due to isolated incidents of intussusception (=telescoping of the bowel) as an object example.

Consider: the vaccine MAY have caused a couple of incidents (which granted, were serious) – but on the whole was protective, and well tolerated. The publication referred to has this as the relative risk:

“…epidemiologic evidence supports a causal relationship, with a population attributable risk of  1 per 10 000 (range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in 12 000) vaccine recipients.”

1 per 10 000 (range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in 12 000) vaccine recipients.”

While this may be an unacceptable risk in a North American community – which is where it was tested, where children mostly just get sick from rotavirus infection – what about in a developing country, where the risk of an infant dying from rotavirus diarrhoea is far higher than 1 / 10 000? Indeed, the same article says:

“Because perceptions of vaccine safety derive from the relative disease burdens of the illness prevented and adverse events induced, the acceptance of rare adverse events may vary substantially in different settings. [ my emphasis]”

Yes – like the vaccine may well have done a great deal of good, and very little harm, in a developing country setting where rehydration therapy is not the norm. But it was pulled, and the world had to wait for Merck’s Rotateq pentavalent live vaccine and GSK’s Rotarix tetravalent live vaccine, YEARS later, and probably a lot of children died that may not have needed to.

I note that the Merck product has this as a warning, too:

“In post-marketing experience, intussusception (including death) and Kawasaki disease have been reported in infants who have received RotaTeq”.

So the vaccine has the same risk profile as Wyeth’s – yet it has been widely distributed, and is apparently highly effective – as is Rotarix. In fact, in 2009 the WHO issued a recommendation “…that health authorities in all nations routinely vaccinate young children against rotavirus…”.

And then…news that must have made many a heart sink, in March 2010:

“GlaxoSmithKline’s oral rotavirus vaccine Rotarix has been temporarily shelved in the U.S. due to a pig-virus contamination. Researchers stumbled on DNA from porcine circovirus type 1–believed nonthreatening to humans–while using new molecular detection techniques. More work is being done to determine whether the whole virus or just DNA pieces are present.

Additional testing has confirmed presence of the matter in the cell bank and seed from which the vaccine is derived, in addition to the vaccine itself. So the vaccine has been contaminated since its early stages of development.”

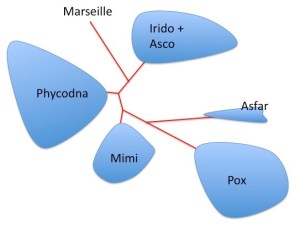

The finding of the porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV-1) DNA in the vaccine was due to what seems to have been publication of an academic investigation in February 2010 of “Viral Nucleic Acids in Live-Attenuated Vaccines” by Eri L Delwart and team, mainly from Blood Systems Research Institute and University of California, San Francisco. They used deep sequencing and microbial array technology to:

“…examine eight live-attenuated viral vaccines. Viral nucleic acids in trivalent oral poliovirus (OPV), rubella, measles, yellow fever, varicella-zoster, multivalent measles/mumps/rubella, and two rotavirus live vaccines were partially purified, randomly amplified, and pyrosequenced. Over half a million sequence reads were generated covering from 20 to 99% of the attenuated viral genomes at depths reaching up to 8,000 reads per nucleotides.”

And they found:

“Mutations and minority variants, relative to vaccine strains, not known to affect attenuation were detected in OPV, mumps virus, and varicella-zoster virus. The anticipated detection of endogenous retroviral sequences from the producer avian and primate cells was confirmed. Avian leukosis virus (ALV), previously shown to be noninfectious for humans, was present as RNA in viral particles [!!], while simian retrovirus (SRV) was present as genetically defective DNA.”

Whooooo…possibly live animal retroviruses in human vaccines?? But most importantly for our purposes:

“Rotarix, an orally administered rotavirus vaccine, contained porcine circovirus-1 (PCV1), a highly prevalent nonpathogenic pig virus, which has not been shown to be infectious in humans. Hybridization of vaccine nucleic acids to a panmicrobial microarray confirmed the presence of endogenous retroviral and PCV1 nucleic acids.”

I don’t know about you, but I’d be more worried about the retroviruses! The authors concluded [my emphases in bold and red]:

“Given that live-attenuated viral vaccines are safe, effective, and relatively inexpensive, their use against human and animal pathogens should be encouraged. The application of high-throughput sequencing and microarrays provides effective means to interrogate current and future vaccines for genetic variants of the attenuated viruses and the presence of adventitious viruses. The wide range of sequences detectable by these methods (endogenous retroviruses, bacterial and other nucleic acids whose taxonomic origin cannot be determined, and adventitious viruses, such as PCV1) is an expected outcome of closer scrutiny to the nucleic acids present in vaccines and not necessarily a reflection of unsafe products. In view of the demonstrated benefit and safety of Rotarix, the >implications (if any) for current immunization policies of the detection of PCV1 DNA of unknown infectivity for humans need to be carefully considered.”

So they find all these bits of adventitious nucleic acids in a live human vaccine, then tell us it’s all right? They go to say, however:

“As an added note, recent testing by GSK indicates that PCV1 was also present in the working cell bank and viral seed used for the generation of Rotarix used in the extensive clinical trials that demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this vaccine. These trials indicate a lack of detectable pathogenic effects from PCV1 DNA on vaccinees.”

So: a clinical trial in retrospect, then?? Interesting idea, that – it’s OK because they inadvertently tested it already and no obvious harm came of it! Mind you, the same thing happened with SV40 in poliovirus vaccines over a lot longer period and on a much larger scale – and while the jury is still out on long-term effects, it appears as though there were none.

The first outcome of the finding, though, was that the FDA recommended in March that use of Rotarix be suspended, pending further investigations.

The same GSK press release reminds us that:

“Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe gastroenteritis among children below five years of age and it is estimated that more than half a million children die of rotavirus gastroenteritis each year – a child a minute [my bold – Ed]. It is predicted that rotavirus vaccination could prevent more than 2 million rotavirus deaths over the next decade. The continued availability of rotavirus vaccines around the world remains critical from a public health perspective to protect children from rotavirus disease. “

Cementing the risk/benefit argument very firmly and pre-emptively, then!

The next development was that Merck’s Rotateq, initially thought to be free of PCVs, was found to contain both PCV-1 AND PCV-2 DNA. From their press release:

“In March 2010, an independent research team and the FDA tested for PCV DNA in rotavirus vaccines; at that time, PCV DNA was not detected in ROTATEQ by the assays that were used initially. Subsequently, Merck initiated PCV testing of ROTATEQ using highly sensitive assays. Merck’s testing detected low levels of DNA from PCV1 and PCV2 in ROTATEQ. Merck immediately shared these results with the FDA and other regulatory agencies.”

Alarming at first sight – but a variety of someones had done their relative risk calculations, and by mid-May, both vaccines had been cleared by the FDA – much to Merck and GSK stockholder relief, one imagines.

“The agency’s decision follows a May 7 recommendation from an FDA advisory panel, which said the PCV contamination didn’t appear to be harmful to humans and the vaccines’ benefits outweighed any “theoretical” risk the products might pose.

In announcing its decision, FDA said that both vaccines have strong safety records, including clinical trials of the vaccines in tens of thousands of patients, plus clinical experience with their administration in millions more. PCV isn’t known to cause illness in humans, whereas the rotavirus these vaccines ward off can cause severe illness and even death.”

All in all, what appears to be a sensible, logical decision, based on evidence – whether collected in retrospect or not – and common sense. After all, as GSK points out in a press release,

“[PCV] is found in everyday meat products and is frequently eaten with no resulting disease or illness.”

Like plant viruses in vegetables, retroviruses in undercooked chicken and other meat, and a myriad other viruses and bacteria that live in, on, and with us – you really can’t keep away from everything.

But there’s still a good case to be made for killed vaccines….

1 per 10 000 (range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in 12 000) vaccine recipients.”

1 per 10 000 (range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in 12 000) vaccine recipients.”