I am TRYING to write an eBook on influenza, which stubbornly refuses to be finished – as part of a sabbatical project, which finished in December 2010. So, like my History of Virology, I am trialling the material on you, the Web community. Enjoy / comment / be enlightened / whatever!

NEW NOTE: The ebook is finished, and is available here on the iBooks Store: please try it out (you can read it on any Mac / iPad / iPhone using the free iBooks app)

History of Influenza

A useful online history in pictorial form can be accessed here.

While they were not recognised as such at the time, major or pandemic outbreaks of influenza disease have occurred throughout recorded history. Medical historians have used contemporary reports to identify probable influenza epidemics and pandemics from as early as 412 BCE – and the term “influenza” was first used in 1357 CE, describing the supposed “influence” of the stars on the disease. The first convincing report of an epidemic of the disease was from 1694, and reports of epidemics and pandemics in the 18th century increased in quality and quantity.

The first pandemic that historians agree on was in 1580: this started in Asia, and spread to Africa, took in the whole of Europe in 6 months, and even got to the Americas. Subsequent pandemics with significant death rates occurred in 1729 and 1781-2; there was a major pandemic in 1880-1883 that attacked up to 25% of affected populations, and another in 1898-1900 that was probably H2N2. There is an excellent account here of the first “modern” pandemic, in 1890 – or at least, the first one to be followed essentially in real time via newspapers.

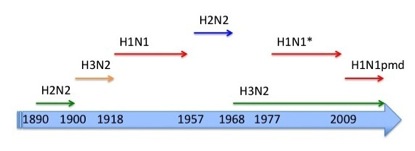

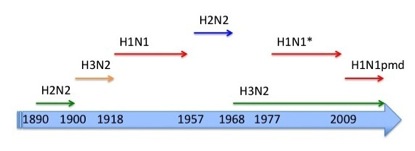

Influenza A pandemics in modern times. * = probably reintroduced from a laboratory from the H1N1 circulating from 1918 until 1957.

The “Spanish Flu” Pandemic 1918-1920

While the first reports of this pandemic were from Spain, this was largely because theirs was possibly the only uncensored press in Europe at the time because of the 1914-1918 War. In fact, it seems generally accepted that the virus originated in the United States, possibly in a military camp, and was then taken via infected personnel travelling by troop transport, to France by April 1918. The virus spread quickly across Europe, and via troop transports again to northern Russia, north Africa and India. Further spread then occurred, to China, New Zealand and The Philippines, all by June 1918.

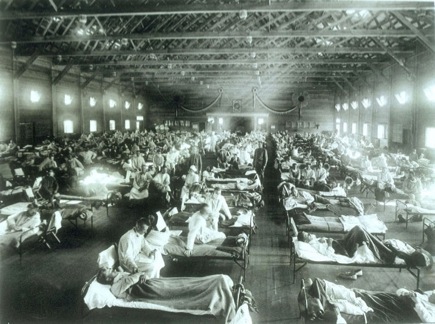

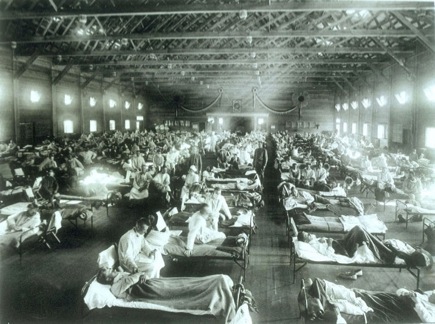

Historical photo of the 1918 Spanish influenza ward at Camp Funston, Kansas, showing the many patients ill with the flu

Initially, there was nothing unusual: infections spread quickly for a while and then declined, and death rates were not higher than in previous pandemics. However, from August 1918 – marked by a ship-borne outbreak in Sierra Leone in west Africa – the virus seemed to have become markedly more virulent, and the death rate is supposed to have increased 10-fold. The virus quickly spread through Europe, to the USA, to India by October 1918, and to Australia by January 1919, all the while spreading through and around Africa.

Some countries had second and even third waves of infection, in 1918-1919 and 1919-1920. The pandemic was initially calculated as having killed some 20 million people: however, later estimates which took into account in particular the African, Indian and Chinese death tolls have increased the death toll to at least 50 million, and possibly up to 100 million.

The virus probably infected over one third of the humans alive at the time, with a case mortality rate of up to 5%. Some regions, like Alaska and parts of Oceania, had death rates of up to 25% of the total population. By contrast, the normal mortality rate for seasonal flu is 0.1 – 0.3% of those infected.

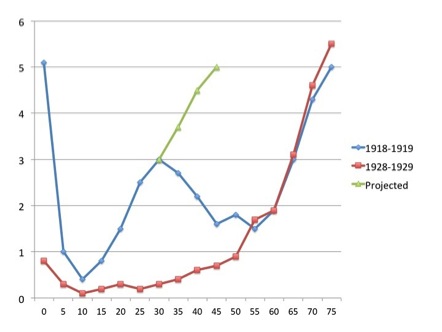

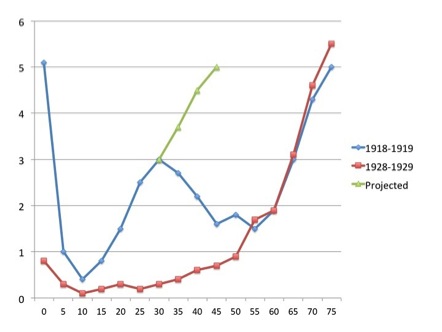

The pandemic was unusual in that it seemed to affect mainly young adults: The graph shows case mortality rates in percent for pneumonia and influenza combined for 1918-1919, and for seasonal influenza for 1928-1929, for different age groups. The “W” shape for the 1918-1919 figures is most unusual; the later seasonal data show a far more usual “U” curve. The green line shows what could have happened if – as is suspected – people over 30 had not had some immunity to the virus, due to prior exposure to the H1 and/or N1 – possibly during the 1880 or 1893 pandemics.

Although secondary bacterial infections of the lungs were common in fatal cases in 1918, and contributed significantly to mortality, there were also many cases of rapid death where bacterial infection could not be demonstrated – so these were due to a so-called “abacterial pneumonia”. Incidentally, the archiving of pathology specimens from especially military cases in the USA proved invaluable in “viral archeology” studies as late as 1997.

Discovery of Influenza Virus

As early as 1901, investigators had shown that the agent of fowl plague was a “filterable virus”: however, this was not linked to human disease, as it was only shown to be an influenza virus in 1955.

Charles Nicolle and Charles Lebailly in France proposed in 1918 that the causative agent of the Spanish Flu was a virus, based on properties of infectious extracts from diseased patients. Specifically, they found that the infectious agent was filterable, not present in the blood of an infected monkey, and caused disease in human volunteers. However, many scientists still doubted that influenza was a viral disease.

A paper presented in 1918 to the Academie Francaise, describing the influenza agent as a filterable virus

In 1931, Robert Shope in the USA managed to recreate swine influenza by intranasal administration of filtered secretions from infected pigs. Moreover, he showed that the classic severe disease required co-inoculation with a bacterium – Haemophilus influenza suis – originally thought to be the only agent. He also pointed out the similarities between the swine disease and the Spanish Flu, where most patients died of secondary infections.

Pigs in the USA and elsewhere probably caught the H1N1 “Spanish Flu” from people – and it has circulated in them continuously until the present day

Patrick Laidlaw and others, working in the UK at the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), reported in 1933 that they had isolated a virus from humans infected with influenza from an epidemic then raging. They had done this by infecting ferrets with filtered extracts from infected humans – after an observation that ferrets could catch canine distemper – and then found that ferrets could transmit influenza to investigators by sneezing on them! The “ferret model” was very valuable, as strains and serotypes of influenza virus could be clinically distinguished from one another. Their serotype was named “influenza A”, and it was later typed as H1N1: this virus was a direct descendant of the Spanish flu virus, and had circulated in humans since 1918. It was the same subtype, incidentally, as that isolated by Shope from pigs.

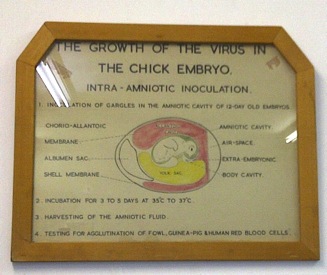

Frank Macfarlane Burnet from Australia in 1936 showed that it was possible to do “pock assays” for influenza virus on the chorioallantoic membranes of fertilised chicken eggs, and subsequently said that:

“It can probably be claimed that, excluding the bacteriophages, egg passage influenza virus can be titrated with greater accuracy than any other virus.”

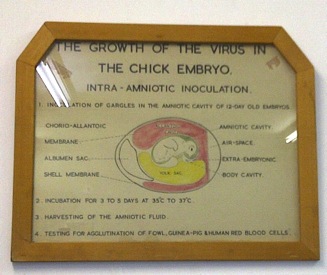

Historic picture on the wall in the routine influenza isolation laboratory at the National Institute of Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg.

This finding led directly to the development of the first influenza A vaccine – a killed virus preparation made in eggs – by Thomas Francis in the USAin late 1943. He had earlier, in 1940, isolated the first influenza B, which was made into a vaccine by 1945. It was then clear that seasonal influenza was caused by two viruses: the A H1N1 type, and influenza B.

The “Asian Flu” of 1957-1958

After the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920, influenza went back to its usual seasonal pattern – until the pandemic of 1957. This started with the news that an epidemic in Hong Kong had involved 250 000 people in a short period. This was a unique event in the history of influenza, as for the first time the rapid global spread of the virus could be studied by laboratory investigation. The virus was quickly identified as an H2N2 subtype.

Except for people over 70, who had possibly been exposed to an influenza pandemic in 1898 – also probably a H2N2 pandemic – the human population was again confronted by a virus that was new to it – and again, the virus alone could cause lethal pneumonia. However, better medical investigation showed that chronic heart or lung disease was found in most of these patients, and women in the third trimester of pregnancy were also vulnerable.

The 1957 pandemic was the first opportunity for medical people to observe the vaccination response in the many people who had not previously been exposed to the novel virus. This was very different to the 1918 virus that had been circulating ever since, meaning that most people had no immunity to it at all. More vaccine was initially needed to give protective immunity than with the earlier type A vaccines. However, by 1960 as the virus recurred as a seasonal infection, immunity levels in the general population increased and vaccine responses were better, due to “priming” of the response by natural infection or first immunisation.

The death toll for this pandemic was around two million people – even though a vaccine was available by late 1957. Infections were most common among school children, young adults, and pregnant women in the early pandemic. Elderly people had the highest death rates, even though this was the only group that had any prior immunity, and there was a second wave in this group in 1958.

The new H2N2 virus completely replaced the previous H1N1 type, and became the new seasonal influenza type.

The “Hong Kong Flu” of 1968 – 1969

This pandemic started in mid-1968 in Hong Kong, and rapidly spread in a few months to India, the Philippines, Australia, Europe and the USA. By 1969, it had reached Japan, Africa and South America. Worldwide, the death toll peaked in December – January. However, although around one million people died, the death rate was lower than in 1957 – 1958 for a number of reasons, including the following:

The virus was similar in some respects to the Asian Flu variant – it was an H3N2 isolate, similar to the pre-1918 seasonal type, sharing N2 – meaning people infected then had partial immunity

The better availability of antibiotics meant secondary bacterial infections were less of a problem.

A vaccine to the new virus became available a month after the epidemic peaked in the USA – following a trend which had started with the 1958 pandemic, of vaccines becoming available only after the peak of the pandemic had passed.

An interesting development soon after this was the finding that waterfowl are the natural hosts of all influenza A viruses – and that there was a greater diversity of viruses in birds than in humans.

The “Red Flu” of 1977

Between May and November of 1977, an epidemic of influenza spread out of north-eastern China and the former Soviet Union – hence the name “Red Flu”. The disease was, however, limited to people under the age of 25 – and was generally mild. It was soon found that virus responsible was effectively identical to the H1N1 that had circulated from 1918 through to 1958, and which had been replaced by the Asian flu, which was in turn supplanted by the Hong Kong flu. This was a most unlikely scenario, given that it was already known that influenza A viruses mutated rapidly as they multiplied – and it had been twenty years since the Spanish or H1N1 flu had been seen in humans. It also explained why infections were limited to young people: anyone who had caught the seasonal flu prior to 1958 was protected.

There has been speculation that the pandemic was due to an inadequately-inactivated or attenuated vaccine released in a trial; there has even been mention of escape from a freezer in a biological warfare lab. There is no firm evidence for either possibility; however, the result is that the virus that had reappeared then co-circulated with the H3N2 as a seasonal virus, continuously until the next pandemic. This was unusual, as a pandemic virus usually becomes the next seasonal strain.

The “Swine Flu” of 2009

The next major pandemic to follow on from the 1968 outbreak was again a type A H1N1 virus – which this time, originated in Mexico or the south-western USA, and probably came directly from intensively-farmed pigs. This had been an unusually long interval between pandemics, and warnings of the coming plague had been issued regularly for years: however, it had been expected that the next pandemic would involve the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1, which had been popping up since 1997, and had been established as an endemic virus in farmed chickens since 2004. This was therefore rather a surprise – but a reasonably welcome one, as the virus turned out to be relatively mild in its effects.

Intensive research on the origin of the virus threw up some very interesting results: it was effectively a direct descendant of the original Spanish flu H1N1 virus, but which had been circulating in pigs ever since 1918 – and had had contributions of genetic material from swine, humans and birds (see Chapter 3, here).

By June 2009 the World Health Organisation had raised the pandemic alert level to Phase 6 – the highest level, indicating that the virus had spread worldwide and that there were infected people in most countries. The “swine flu” pandemic was not as serious as had been feared, however: symptoms of infection were similar to seasonal influenza, albeit with a greater incidence of diarrhoea and vomiting. The virus was also found to preferentially bind to cells deeper in the lungs than seasonal viruses: this explained both why it was generally mild – it did not often get that far down – but also why it could be fatal, as it could cause severe and sudden pneumonia if it did penetrate deep enough, similar to the 1918 influenza. Binding to cells in the intestines also explained the unusual nausea and vomiting. It was also found that there were distinct high-risk groups, including pregnant women and obese individuals. In these respects it was similar to the 1918 flu, as this also predominantly affected young people, and pregnant mothers.

Vaccine manufacture was initiated in June 2009 by the WHO and manufacturers: while there was some concern over the slower-than-normal growth rate of the vaccine strains of the virus, this was rectified in a few months. However, as also happened with the other pandemics, there was not enough vaccine made soon enough to deal effectively with the pandemic – even though similarities between the pandemic virus and the 1977 outbreak virus meant that most middle-aged people had pre-existing immunity to it, which either prevented infection, or reduced the severity of infections. This also meant a single dose was sufficient in adults, similar to the seasonal vaccine.

While the disease may have been mild in most cases, and initially the death toll was thought to be low, by 2012 it was calculated that 300 000 or more people probably died, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia. A sobering quote: “since the people who died were much younger than is normally the case from influenza, in terms of years of life lost the H1N1 pandemic was significantly more lethal than the raw numbers suggest”. The virus has now become a normal seasonal strain, replacing the previously-circulating H1N1, but interestingly, has not replaced the H3N2 that has circulated since 1968.

All material Copyright EP Rybicki, except for the Camp Funston image, which is in the public domain.