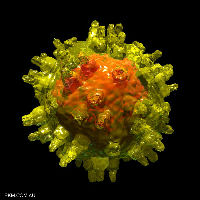

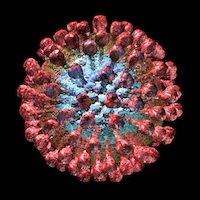

Lassa fever is a nasty acute viral haemorrhagic fever (HF), caused by Lassa virus. This is a member of the genus Arenavirus, family Arenaviridae, comprising a collection of 2-component ss(-)RNA enveloped viruses which also includes Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus – a favourite model organism – and a host of South American HF viruses. It is also a BSL-4 pathogen, or “hot virus” – one that needs to be worked with in a spacesuit environment, meaning it is pretty difficult to study in the lab.

Arenaviruses are interesting for molecular virologists because of they are one of several ssRNA(-)RNA viruses with “ambisense” genomes, meaning their genomic RNAs have stretches which can be directly read into protein by ribosomes, instead of having to be transcribed first.

The virus and the fever are endemic in the West African countries of Nigeria – from where it was first described in 1969 – Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea and the Central African Republic, but almost certainly occur more widely. There are an estimated 300 000 cases a year, with 5 000 deaths attributed to the virus annually – again, probably an underestimate, as in epidemics mortality can go up to 50%. The virus is vectored by what is probably the most common type of rodent in equatorial Africa, multimammate rats in the genus Mastomys, mainly via aerosolised faces and urine, which contain high concentrations of virions. The rat can maintain infection as a persistent asymptomatic state. It is also possible to spread the disease from person to person, via body fluids.

The CDC has this to say about Lassa fever:

In areas of Africa where the disease is endemic (that is, constantly present), Lassa fever is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. While Lassa fever is mild or has no observable symptoms in about 80% of people infected with the virus, the remaining 20% have a severe multisystem disease. Lassa fever is also associated with occasional epidemics, during which the case-fatality rate can reach 50%.

While this may seem to be of mild interest only to the international community – after all, it is a seasonal disease limited to one part of Africa, and only 5 000 people die annually, compared to 400 000+ for influenza – it is and remains a nasty disease, with significant side effects, which include temporary or permanent deafness in those who recover – various degrees of deafness occur in up to one-third of cases – and spontaneous abortion of about 95% of third trimester foetuses in infected mothers, and a death rate of >80% in the women. Moreover, while the term “limited to West Africa” may make it sound of local interest only, it is worth noting that that part of Africa is bigger than the whole of Western Europe – in fact, it’s the size of the whole of the USA – and is home to close to 200 million people. Moreover, there is serious concern that the incidence of Lassa fever may be increasing, and that it is emerging from its endemic regions into newer pastures with changing regional weather patterns. However, while fears of rampant spread via air travel do exist, like “Ebola Preston“, these are largely scare stories – which are admirably efficiently debunked here.

A tragic fact about Lassa fever is that it is treatable with drugs, if caught early: JB McCormick and others showed in 1986 that intravenous ribavirin given within 6 days of the onset of fever reduced mortality of patients with a serum aspartate aminotransferase level greater than or equal to 150 IU per litre at the time of hospital admission, from 55% to 5% – whereas patients whose treatment began seven or more days after the onset of fever had a case-fatality rate of 26 percent. Moreover, oral ribavirin was also effective in patients at high risk of death.

So WHY isn’t ribavirin distributed widely and freely in West Africa for use in clinics?? Why, indeed…that doyen of the US biowarfare / hot virus community, CJ Peters, had this to say in an online book:

Both antiviral vaccines and drugs suffer from major development problems. They would require an expensive developmental effort that has never been able to attract industrial support based on disease activity in endemic areas, even when the U.S. Department of Defense has expressed an interest and provided an additional market.

In other words, no-one would manufacture it for a market that couldn’t pay for it in a sustainable way – another of the unacceptable faces of modern capitalism.

There is hope, however – people are working on vaccines, and there have been significant successes in primate models: in 2005, Geisbert et al. described a

“…replication-competent vaccine against Lassa virus based on attenuated recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors expressing the Lassa viral glycoprotein. A single intramuscular vaccination of the Lassa vaccine elicited a protective immune response in nonhuman primates against a lethal Lassa virus challenge. Vaccine shedding was not detected in the monkeys, and none of the animals developed fever or other symptoms of illness associated with vaccination. The Lassa vaccine induced strong humoral and cellular immune responses in the four vaccinated and challenged monkeys. Despite a transient Lassa viremia in vaccinated animals 7 d after challenge, the vaccinated animals showed no evidence of clinical disease.”

Very promising, at first glance. This is, however, a live virus vaccine – with all of the attendant problems of purification of whole virus, contamination, manufacture, cold chain – and cost…. Given the recent global experience with virus vaccines both live and dead – and recent rotavirus and papillomavirus vaccines would be excellent recent examples, with unit costs at over US$40 per shot – this vaccine will not debut, if it does so at all, at a cost that is even remotely affordable in the target market in West Africa.

Unless the target market is in fact the US military – which, given the fact that the lead author’s address is given as “Virology Division, United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick”, can be considered quite likely.

Another more recent, and – to my biased mind at least – more promising candidate vaccine, is one described by Luis M Branco et al. in a brand-new Virology Journal article. This one is also associated with the US military – with 3 of 11 authors with addresses “@usarmy.mil” – but describes a virus-like particle vaccine candidate rather than a recombinant live virus.

Lassa virus-like particles displaying all major immunological determinants as a vaccine candidate for Lassa hemorrhagic fever

Virology Journal 2010, 7:279 doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-279

Published: 20 October 2010

Luis M Branco, Jessica N Grove, Frederick J Geske, Matt L Boisen, Ivana J Muncy, Susan A Magliato, Lee A Henderson, Randal J Schoepp, Kathleen A Cashman, Lisa E Hensley and Robert F Garry

Background

Lassa hemorrhagic fever (LHF) is a neglected tropical disease with significant impact on the health care system, society, and economy of Western and Central African nations where it is endemic. Treatment of acute Lassa fever infection with intravenous Ribavirin, a nucleotide analogue drug, is possible and greatly efficacious if administered early in infection. However, this therapeutic platform has not been approved for use in LHF cases by regulatory agencies, and the efficacy of oral administration has not been demonstrated. Therefore, the development of a robust vaccine platform generated in sufficient quantities and at a low cost per dose could herald a subcontinent-wide vaccination program. This would move Lassa endemic areas toward the control and reduction of major outbreaks and endemic infections. To date, several potential new vaccine platforms have been explored, but none have progressed toward clinical trials and commercialization. To this end, we have employed efficient mammalian expression systems to generate a Lassa virus (LASV)-like particle (VLP)-based modular vaccine platform.

Results

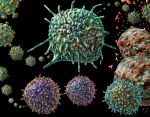

A mammalian expression system that generated large quantities of LASV VLP in human cells at small scale settings was developed. These VLP contained the major immunological determinants of the virus: glycoprotein complex, nucleoprotein, and Z matrix protein, with known post-translational modifications. The viral proteins packaged into LASV VLP were characterized, including glycosylation profiles of glycoprotein subunits GP1 and GP2, and structural compartmentalization of each polypeptide. The host cell protein component of LASV VLP was also partially analyzed, namely glycoprotein incorporation, though all host cell components remain largely unknown. All combinations of LASV Z, GPC, and NP proteins that generated VLP did not incorporate host cell ribosomes, a known component of native arenaviral particles, despite detection of small RNA species packaged into pseudoparticles. Although VLP did not contain the same host cell components as the native virion, electron microscopy analysis demonstrated that LASV VLP appeared structurally similar to native virions, with pleiomorphic distribution in size and shape. LASV VLP that displayed GPC or GPC+NP were immunogenic in mice, and generated a significant IgG response to individual viral proteins over the course of three immunizations, in the absence of adjuvants. Furthermore, sera from convalescent Lassa fever patients recognized VLP in ELISA format, thus affirming the presence of native epitopes displayed by the recombinant pseudoparticles.

Conclusions

These results established that modular LASV VLP can be generated displaying high levels of immunogenic viral proteins, and that small laboratory scale mammalian expression systems are capable of producing multi-milligram quantities of pseudoparticles. These VLP are structurally and morphologically similar to native LASV virions, but lack replicative functions, and thus can be safely generated in low biosafety level settings. LASV VLP were immunogenic in mice in the absence of adjuvants, with mature IgG responses developing within a few weeks after the first immunization. These studies highlight the relevance of a VLP platform for designing an optimal vaccine candidate against Lassa hemorrhagic fever, and warrant further investigation in lethal challenge animal models to establish their protective potential.

So what they have done is to make non-infectious particles which strongly resemble native virions of Lassa virus, at high yield in a mammalian cell expression system, under low containment conditions – meaning it is safe for workers. The VLPs are highly and appropriately immunogenic, and appear to have significant potential as a Lassa virus vaccine. This is very similar to previously reported work on Rift Valley fever VLPs made in insect cells, and HPAI and pandemic influenza HA-containing VLPs made in plants, in that VLPs are produced at good yield in an established expression system.

Except that they’re using mammalian cells, with all of the cost implications inherent in that. And they’re using transfection of plasmids – not the world’s cheapest method of producing proteins. And they didn’t show efficacy….

Ah, well, there’s still hope – and they could still go green…B-)

1 per 10 000 (range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in 12 000) vaccine recipients.”

1 per 10 000 (range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in 12 000) vaccine recipients.”