28th April 2009:

It just HAD to happen.

There was the world’s attention, focussed on H5N1 bird flu from Asia as The Next Big One – including doom and gloom pronouncements from right here (and here) – and of course, another flu comes from another source, in another location entirely. You can, however, as previously highlighted here in ViroBlogy, use Google “Flu Trends” to track it – and now Google Maps too (thanks, Vernon!).

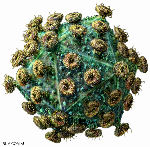

So what do we know? On the 27th of April, the Mexican government admitted to some 150 deaths, and over 1600 people apparently infected, in an epidemic caused by an Influenza A H1N1 virus that appeared to be a reassortant of viruses from pigs, birds and humans. The virus has been dubbed “swine flu”; however, there is doubt as to whether it has been shown to even infect pigs, let alone been found in them, and it probably ought to be known as “Mexico Flu”. There is the problem, of course, that apparently parts of the virus – and the N1 gene in particular – are of Eurasian swine flu origin, so exactly where it comes from may be forever obscure.

As for current expert knowledge, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) have set up dedicated pages to track the potential pandemic – because that is what they are calling it.

The WHO has, as of the 27th April,

“…raised the level of influenza pandemic alert from the current phase 3 to phase 4.

Swine Flu: Understanding the WHO’s Global Pandemic-Alert Levels – Health Blog – WSJ via kwout

The change to a higher phase of pandemic alert indicates that the likelihood of a pandemic has increased, but not that a pandemic is inevitable.

As further information becomes available, WHO may decide to either revert to phase 3 or raise the level of alert to another phase.

This decision was based primarily on epidemiological data demonstrating human-to-human transmission and the ability of the virus to cause community-level outbreaks.

Given the widespread presence of the virus, the Director-General considered that containment of the outbreak is not feasible. The current focus should be on mitigation measures.”

All of which begs the questions: what IS it, and how BAD is it?? We know that by the 28th April, the virus had been confirmed in the USA (>40 cases), Spain, Canada, and according the the BBC, the UK, Brazil and New Zealand as well.

While financial markets are panicking , airlines are cancelling flights, and people in Mexico appear to be dying, people infected in the USA seem only to be getting ill, and then recovering.

The bad news is that the virus haemagglutinin – the H1 – is probably only distantly related to that of the currently circulating human variant, so the flu vaccines on release right now will be of only limited efficacy.

The good news – especially for Roche and GlaxoSmithKline – is that the antivirals Tamiflu and Relenza seem to work against the virus.

29th April 2009

The virus continues to spread: according to the WHO site,

“As of 19:15 GMT, 28 April 2009, seven countries have officially reported cases of swine influenza A/H1N1 infection. The United States Government has reported 64 laboratory confirmed human cases, with no deaths. Mexico has reported 26 confirmed human cases of infection including seven deaths. The following countries have reported laboratory confirmed cases with no deaths – Canada (6), New Zealand (3), the United Kingdom (2), Israel (2) and Spain (2).

….

WHO advises no restriction of regular travel or closure of borders. It is considered prudent for people who are ill to delay international travel and for people developing symptoms following international travel to seek medical attention, in line with guidance from national authorities.“There is also no risk of infection from this virus from consumption of well-cooked pork and pork products. Individuals are advised to wash hands thoroughly with soap and water on a regular basis and should seek medical attention if they develop any symptoms of influenza-like illness.

Of course, there is also the inevitable hype – and some humour (thanks, Suhail!):

With a byline reminiscent of the “Ebola Preston” which was coined to satirise the hype generated around the 1995 Ebola hype, we have

- “Scare Flu spreads from tabloids to the broadsheets” and

- “Swine flu caused by poverty, not pigs, says Mbeki” from our very own Hayibo.com.

30th April 2009:

…so of course, I talk to a journalist; and of course, I shouldn’t have…! For an otherwise good article about pandemic preparedness in Africa [ignore the bit about no drug stockpile in South Africa, because apparently we have some], see here. South Africans: look at info on influenza at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) in Johannesburg.

The WHO yesterday raised the level of influenza pandemic alert from the current phase 4 to phase 5. We owe the WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan, for these comments:

“On the positive side, the world is better prepared for an influenza pandemic than at any time in history.

Preparedness measures undertaken because of the threat from H5N1 avian influenza were an investment, and we are now benefitting from this investment.

For the first time in history, we can track the evolution of a pandemic in real-time.”

From the BBC today:

In Mexico, the epicentre of the outbreak, the number of confirmed cases rose to 97 – up from 26 on Wednesday….

- The Netherlands confirms its first case of swine flu, in a three-year-old boy recently returned from Mexico. Cases have also been confirmed in Switzerland, Costa Rica and Peru

- The number of confirmed cases in the US rose to 109 in 11 states

- Japan reported its first suspected case of swine flu

- China’s health minister says that the country’s scientists have developed a “sensitive and fast” test for spotting swine flu in conjunction with US scientists and the WHO. The country has recorded no incidence of the flu yet.

- The WHO says it will now call the virus influenza A (H1N1).

And first prize for over-reaction of the year:

On Wednesday, Egypt began a mass slaughter of its pigs – even though the WHO says the virus was now being transmitted from human to human [and there is no evidence it was ever transmitted between pigs].

About half the world’s oxygen is being produced by tiny photosynthesising creatures called phytoplankton in the major oceans. These organisms are also responsible for removing carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and locking it away in their bodies, which sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die, removing it forever and limiting global warming.

About half the world’s oxygen is being produced by tiny photosynthesising creatures called phytoplankton in the major oceans. These organisms are also responsible for removing carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and locking it away in their bodies, which sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die, removing it forever and limiting global warming.

the viruses being very similar in genome organisation and indeed genome sequence.

the viruses being very similar in genome organisation and indeed genome sequence.