Our Department has a journal club every Friday, when research folk (staff and students) get together to hear a postgrad student present an interesting new paper. Last Friday Alta Hattingh from my lab gave a thought-provoking and insightful presentation on whether or not smallpox virus should be destroyed – so I asked her to turn it into a blog post.

Should remaining stockpiles of smallpox virus (Variola) be destroyed?

Raymond S. Weinstein

Emerging Infectious Diseases (2011), Vol 17(4): 681 – 683

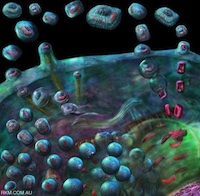

Smallpox virus replication cycle. Russell Kightley Media

Smallpox is believed to have emerged in the Middle East approximately 6000 to 10 000 years ago and is one of the greatest killers in all of human history, causing the death of up to 500 million people in the 20th century alone. Smallpox is the first virus to ever be studied in detail and it is also the first virus for which a vaccine was developed. Smallpox was beaten by the Jenner vaccine (first proposed in 1796) and the disease was declared eradicated in 1980 in one of the greatest public health achievements in human history.

The last officially acknowledged stocks of variola are held by the United States at the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (consisting of 450 isolates) and in Russia at the State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology (various sources place the number of specimens at ~150 samples, consisting of 120 strains). This includes strains that were collected during the Cold War as potential for biological weapons due to their increased virulence. Then, there is also the added possibility that stolen smallpox cultures are in the hands of terrorists organizations.

In 2011 the World Health Organisation (WHO) plans to announce its recommendation for the destruction of all known remaining stockpiles of smallpox virus. They have wanted to destroy the virus ever since 1980 when the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Louis Sullivan, promised destruction of US stockpiles within 3 years. This never happened in the US or Russia and no official recommendation for destruction have been recommended by the World Health Assembly. In 2007 the final deadline for a decision was postponed until 2011 as no consensus could be reached among the executive board of the WHO.

The only real benefit that could be gained from destroying all known remaining stockpiles of smallpox virus in the world would be the prevention of causing a lethal epidemic due to theft or accidental release of the virus. However, according to Weinstein destruction would only provide an illusion of safety and that the drawbacks of eliminating variola from existence are many.

In this paper Weinstein mentions the possible reasons behind the hesitance to destroy smallpox. The prolonged existence of smallpox along with the important clinical implications of its high infectivity and mortality rates suggests that the human immune system evolved under the disease’s evolutionary influence. In the last decade research has been done which suggests that variola (and vaccinia) have the ability to alter the host immune response by targeting various components of the immune system. We are only beginning to understand the complex pathophysiology and virulence mechanisms of the smallpox virus. An example of the importance of smallpox in human evolution is the CC-chemokine receptor null mutation (CCR5Δ32), which first appeared in Europe ~3500 years ago one person and today it can be found in ~10% of all those from northern European decent. The mutation prevents expression of the CCR5 receptor on the surface of many immune cells and provides resistance to smallpox. This same mutation also confers nearly complete immunity to HIV. In a recent study done by Weinstein and co-workers (2010) it was postulated that exposure to vaccinia and variola may have previously inhibited successful spread of HIV, suggesting that we swopped out one major disease for another. By eliminating the variola stockpiles from existence on-going research in this direction might be hampered and the possibility future studies employing intact virus will be rendered impossible.

Finally, we are capable of creating a highly virulent smallpox-like virus from scratch or a closely related poxvirus through genetic manipulation. This renders moot any argument for the destruction of remaining stockpiles of smallpox in the belief that it would be for the benefit of protecting mankind.

In an editorial of the Vaccine journal, the editors make a compelling case in favour for the destruction of remaining stockpiles of smallpox virus. To follow is their take on the situation:

Why not destroy the remaining smallpox virus stocks?

Editorial (by J. Michael Lane and Gregory A. Poland)

Vaccine (2011), Vol 29: 2823 – 2824

The Advisory Committee on Variola Virus Research (created in 1998 as part of the WHO) concluded that live variola is no longer necessary except to continue attempts to create an animal model which might mimic human smallpox and assist in the licensure of new generation vaccines and antivirals.

The editors feel that scientific recommendation for keeping smallpox stocks need to be scrutinized and that a number of political and ethical issues need to be addressed. Below are comments by editors on these issues:

Scientific issues:

The smallpox virus is no longer needed to elucidate its genome, 49 strains have been sequenced and published, the editors feel that there is no need to sequence additional strains. The smallpox virus can be destroyed as it is possible to reconstruct it from published sequences or to insert the genes of interest into readily available strains of vaccinia or monkeypox. Refinements regarding diagnostics can be made by using other orthopoxviruses or parts of the smallpox strains already sequenced; vaccines have been produced that are far less reactogenic than the first and second generation of vaccinia vaccines and they are very effective against other orthopoxviruses. Finally, the development of an animal model is difficult to perfect as variola is host-specific, thus there are no guarantees that a model will be found that mimics the pathophysiology of smallpox in humans.

Political/ethical issues:

The US is a supporter of the WHO and the UN and failure to comply with the request of the World Health Assembly jeopardizes the US’s potential to work with the UN to further their foreign policy and population health goals. Biological weapons have been banned from the US military arsenal and there is no way they would use a biological weapons such as smallpox whether it be in offense or defence. The editors reckon that the risk of a biological warfare attack using smallpox is highly unlikely as terrorists who have the knowledge and sophistication to grow and prepare smallpox for dispersal would realize that they could cause harm to their own countries. Apart from that, Western nations have the facilities to isolate and vaccinate against smallpox in a timely manner.

According to the editors there is no ethical way to justify maintaining an eradicated virus. Even though the possibility of accidental release is very small, it is an unacceptable risk. Maintenance of the smallpox virus stocks is expensive and time consuming, it also burdens the CDC without scientific merit and their resources are better used to protect the public from infectious diseases.

In conclusion the editors maintain that the remaining smallpox stocks should be destroyed and the world should make possession of the virus an “international crime against humanity”.

We are presented with two very different views with regards to whether or not smallpox virus stocks should be destroyed forever. The WHO meets again this year to decide the final fate of smallpox. Will the board reach consensus or will the smallpox virus yet again receive a stay of execution?

Note added 1 Oct 2015

Interestingly, I found the following text written by me in my archive of articles – published as a Letter in the now sadly defunct HMS Beagle, in 1999:

HMS Beagle

( Updated May 28, 1999 · Issue 55) http://news.bmn.com/hmsbeagle/55/viewpts/letters

Use logic, not fear

The destruction of all (known) stocks of smallpox virus (Reprieve for a Killer: Saving Smallpox by Joel Shurkin) seems to be a very emotive issue. Perhaps, if people looked at it less in terms of a threat, and more in terms of a resource, most of the problem would go away. For example, although the original article made mention of monkey pox, and how it was almost as dangerous as smallpox, and appeared to be adapting to human-to-human spread, nothing has been said about investigating why smallpox was so much more effective at spreading within human populations than monkey pox is. It is all very well having the smallpox genome sequence; however, without the actual DNA, it is difficult to recreate genome fragments of the size that may be needed to make recombinant viruses to investigate the phenomenon of host/transmission adaptation. Additionally, without the actual virus, it will be impossible to compare the effects of a doctored vaccine strain with the real thing. Destroying known stocks of the virus will not affect the stocks that are most likely to be used for bioterrorism. It will, however, handicap research into ways of combating the virus/understanding how it worked in the first place.