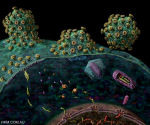

We thank Russell Kightley for permission to use the images

We thank Russell Kightley for permission to use the images

Anna-Lise Williamson and I again hosted the Virology Africa Conference (only the second since 2005!), at the University of Cape Town‘s Graduate School of Business in the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront in Cape Town. While this was a local meeting, with just 147 attendees, we had a very international flavour in the plenaries: of 18 invited talks, 9 were by foreign guests. Plenaries spanned the full spectrum of virology, ranging from discovery virology to human papillomaviruses to HIV vaccines to tick-borne viruses to bacteriophages found in soil to phages used as display vectors, and to viromes of whole vineyards. There were a further 52 contributed talks and 41 posters, covering topics from human and animal clinical studies, to engineering plants for resistance to viruses.

A special 1-day workshop on “Human Papillomaviruses – Vaccines and Cervical Cancer Screening” preceded the main event: this was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche and Aspen Pharmacare, and had around 90 attendees. Anna-Lise Williamson (NHLS & IIDMM, UCT) opened the workshop with a talk entitled “INTRODUCTION TO HPV IN SOUTH AFRICA – SCREENING FOR CERVICAL CANCER AND VACCINES”, and set the stage for Jennifer Moodley (Community Health Dept, UCT) to cover health system issues around the prevention of cervical cancer in SA, and the newly-minted Dr Zizipho Mbulawa (Medical Virology, UCT) to speak on the the impact of HIV infection on the natural history of HPV. This last issue is especially interesting, given that HIV-infected women may have multiple (>10) HPV types and progress faster to cervical malignancies, and HPV infection is a risk factor for acquisition of HIV. The Roche-sponsored guest, Peter JF Snijders (VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam), gave an excellent description of novel cervical screening options using primary HPV testing, to be followed by two accounts of cytological screening in public and private healthcare systems in SA, by Irene le Roux (National Health Laboratory Service) and Judy Whittaker (Pathcare), respectively. Ulf Gyllensten (University of Uppsala, Sweden) described the Swedish experience with self-sampling and repeat screening for the prevention of cervical cancer, especially in groups that are not reached by standard screening modalities. Hennie Botha and Haynes van der Merwe (both University of Stellenbosch) closed out the session with talks on the effect of the HIV pandemic on cervical cancer screening, and a project aimed at piloting adolescent female vaccination against HPV infection in Cape Town.

A special 1-day workshop on “Human Papillomaviruses – Vaccines and Cervical Cancer Screening” preceded the main event: this was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche and Aspen Pharmacare, and had around 90 attendees. Anna-Lise Williamson (NHLS & IIDMM, UCT) opened the workshop with a talk entitled “INTRODUCTION TO HPV IN SOUTH AFRICA – SCREENING FOR CERVICAL CANCER AND VACCINES”, and set the stage for Jennifer Moodley (Community Health Dept, UCT) to cover health system issues around the prevention of cervical cancer in SA, and the newly-minted Dr Zizipho Mbulawa (Medical Virology, UCT) to speak on the the impact of HIV infection on the natural history of HPV. This last issue is especially interesting, given that HIV-infected women may have multiple (>10) HPV types and progress faster to cervical malignancies, and HPV infection is a risk factor for acquisition of HIV. The Roche-sponsored guest, Peter JF Snijders (VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam), gave an excellent description of novel cervical screening options using primary HPV testing, to be followed by two accounts of cytological screening in public and private healthcare systems in SA, by Irene le Roux (National Health Laboratory Service) and Judy Whittaker (Pathcare), respectively. Ulf Gyllensten (University of Uppsala, Sweden) described the Swedish experience with self-sampling and repeat screening for the prevention of cervical cancer, especially in groups that are not reached by standard screening modalities. Hennie Botha and Haynes van der Merwe (both University of Stellenbosch) closed out the session with talks on the effect of the HIV pandemic on cervical cancer screening, and a project aimed at piloting adolescent female vaccination against HPV infection in Cape Town.

The next part of the Workshop overlapped with the Conference opening, with a Keynote address by Margaret Stanley (Cambridge University) on how HPV evades host defences (sponsored by MSD), and another by Hugues Bogaert (HB Consult, Gent, Belgium)) on comparisons of the cross-protection by the two HPV vaccines currently registered worldwide (sponsored by Aspen Pharmacare). Margaret Stanley’s talk was a masterclass on HPV immunology: the concept that such a seemingly simple virus (only 8 kb of dsDNA) could interact with cells in such a complex way, was a surprise for all not acquainted with the viruses. Bogaert’s talk was interesting in view of the fact that the GSK offering, which has only only two HPV types, raises far higher titre antibody responses than the MSD vaccine with four HPV types, AND seems to elicit better cross-protective antibodies: this should help inform choice of product from the individual point of view. However, the fact that MSD seems able to respond better to national healthcare system tenders in terms of price per dose is also a major factor in the adoption stakes.

The Conference proper started with a final address by Barry Schoub, long-time but now retired Director of the National Institute of Virology / National Institute of Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg, and also long-time CEO of the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation (PRF): this is possibly the premier funding agency for anything to do with viruses in South Africa, and a major sponsor of the Conference. He spoke on the history of the PRF, and how it had managed to shepherd an initial endowment of around 1 million pounds in the 1950s, to over ZAR100 million today – AND to dispense many millions in research project and bursary funding in South Africa over several decades.

The first session segued into a welcoming cocktail reception and registration at the Two Oceans Aquarium in the V&A Waterfront: this HAS to be one of the only social events for an academic conference where the biggest sharks are the ones in the tank, and not in the guest list! I think people were suitably blown away – as always, in the aquarium – and the tone was set for the rest of the meeting. The wine and food were good, too.

The first session segued into a welcoming cocktail reception and registration at the Two Oceans Aquarium in the V&A Waterfront: this HAS to be one of the only social events for an academic conference where the biggest sharks are the ones in the tank, and not in the guest list! I think people were suitably blown away – as always, in the aquarium – and the tone was set for the rest of the meeting. The wine and food were good, too.

The first morning session of the conference featured virus hunting and HIV vaccines, as well as plant-made vaccines and more HPV. W Ian Lipkin (Columbia University, USA) opened with “Microbe Hunting” – which lived up to its title very adequately, with discussion of a plethora of infectious agents. As well as of the methods newly used to discover them, which include high-throughput sequencing, protein arrays, very smart new variants on PCR…. I could see people drooling in the audience; the shop window was tempting enough to make one jump ship to work with him without a second thought. He said that probably 99% of vertebrate viruses remain to be discovered, and that advances in DNA sequencing technology were a major determinant in the rapidly-increasing pace of discovery. He made the point that while the emphasis in the lab had shifted from wet lab people to bioinformatics, he thought it would move back again as techniques get easier and more automated – meaning (to me) that there is no substitute for people who understand the actual biological problems. It was interesting that, while telling us of his work on the recently-released blockbuster “Contagion” – where “the virus is the star!” – he showed a slide with a computer in the background running a recombination detection package called RDP, which was designed in South Africa. It can also be seen in the trailer, apparently. Darren Martin will not be looking for royalties or screen credits, however.

The first morning session of the conference featured virus hunting and HIV vaccines, as well as plant-made vaccines and more HPV. W Ian Lipkin (Columbia University, USA) opened with “Microbe Hunting” – which lived up to its title very adequately, with discussion of a plethora of infectious agents. As well as of the methods newly used to discover them, which include high-throughput sequencing, protein arrays, very smart new variants on PCR…. I could see people drooling in the audience; the shop window was tempting enough to make one jump ship to work with him without a second thought. He said that probably 99% of vertebrate viruses remain to be discovered, and that advances in DNA sequencing technology were a major determinant in the rapidly-increasing pace of discovery. He made the point that while the emphasis in the lab had shifted from wet lab people to bioinformatics, he thought it would move back again as techniques get easier and more automated – meaning (to me) that there is no substitute for people who understand the actual biological problems. It was interesting that, while telling us of his work on the recently-released blockbuster “Contagion” – where “the virus is the star!” – he showed a slide with a computer in the background running a recombination detection package called RDP, which was designed in South Africa. It can also be seen in the trailer, apparently. Darren Martin will not be looking for royalties or screen credits, however.

Don Cowan (University of the Western Cape) continued the discovery theme, albeit with bacteriophages as the target rather than vertebrate viruses. It is worth emphasising that phages probably represent the biggest source of genetic diversity on this planet – and given how even the most extreme of microbes have several kinds of viruses, as Don pointed out, it is possible that this extends to neighbouring planets too [my speculation – Ed]. He occupies an interesting niche – much like the microbes he hunts – in that he specialises in both hot and cold terrestrial desert environments, which are drastically understudied in comparison to marine habitats. He made the interesting point that metagenome sequencing studies such as his own generate data that is in danger of being discarded without reuse, given that folk tend to take what they are interested out of it and neglect the rest.

Anna-Lise Williamson (NHLS, IIDMM, UCT) then described the now-defunct SA AIDS Vaccine Initiative vaccine development project at UCT. It is rather sobering to revisit a project that used to employ some 45 people, and had everything from Salmonella, BCG, MVA, DNA and insect cell and plant-made subunit HIV vaccines in the pipeline – and now employs just 5, to service the two vaccines that made it into into clinical trial. The BCG-based vaccines continued to be funded by the NIH, however, and the SA National Research Foundation funds novel vaccine approaches. Despite all the funding woes, the first clinical trial is complete with moderate immunogenicity and no significant side effects, and two more are planned: these are an extension of the first – HVTN073/SAAVI102 – with a Novartis-made subtype C gp140 subunit boost, and the other is HVTN086/SAAVI103, which compprises different commbinations of DNA, MVA and gp140 vaccines.

Anna-Lise Williamson (NHLS, IIDMM, UCT) then described the now-defunct SA AIDS Vaccine Initiative vaccine development project at UCT. It is rather sobering to revisit a project that used to employ some 45 people, and had everything from Salmonella, BCG, MVA, DNA and insect cell and plant-made subunit HIV vaccines in the pipeline – and now employs just 5, to service the two vaccines that made it into into clinical trial. The BCG-based vaccines continued to be funded by the NIH, however, and the SA National Research Foundation funds novel vaccine approaches. Despite all the funding woes, the first clinical trial is complete with moderate immunogenicity and no significant side effects, and two more are planned: these are an extension of the first – HVTN073/SAAVI102 – with a Novartis-made subtype C gp140 subunit boost, and the other is HVTN086/SAAVI103, which compprises different commbinations of DNA, MVA and gp140 vaccines.

It was clear from the talk that if South Africa wants to support local vaccine development, the government needs to support appropriate management structures to enable this – and above all, to provide funding. However, all is not lost, as much of the remaining expertise in several of the laboratories that were involved in the HIV vaccine programme can now involve themselves in animal vaccine projects.

Ed Rybicki made it an organisational one-two with an after-tea plenary on why production of viral vaccines in plants is a viable rapid-response option for emerging or re-emerging diseases or bioterror threats. The talk briefly covered the more than 20 year history of plant-made vaccines, highlighting important technological advances and proofs of concept and efficacy, and concentrated on the use of transient expression for the rapid, high-level expression of subunit vaccines. Important breakthoughs that were highlighted included the development of the Icon Genetics TMV-based vectors, Medicago Inc and Fraunhofer USA’s recent successes with H5N1 and H1N1 HA protein production in plants – and the Rybicki group’s successes with expression of HPV L1-based and E7 vaccine candidates. The talk emphasised how the technology was inherently more easily scalable, and quicker to respond to demand, than conventional approaches to vaccine manufacture – and how it could profitably be applied to “orphan vaccines” such as for Lassa fever.

Ulf Gyllensten had another innings in the main conference, with a report on a study of a possible linkage of gene to disease in HPV infections – which could explain why some people clear infections, and why some have persistent infections. They used the Swedish cancer registry (a comprehensive record since the end of the 1950s) to calculate familial relative risk of cancer of the cervix (CC): relative risk was 2x for a full sister, the same for a mother-daughter pair and the risk for a half sister was 50% higher while risk was not linked to non-biological siblings or parents, meaning the link was not environmental. A preliminary study found HLA alleles associated with CC, and increased carriage of genes was linked to increased viral load. A subsequent genome wide association study using an Omni Express Bead Chip detecting700K+ SNPs yielded one area of major interest, on Chr 6 – this is a HLA locus. They got 3 independent signals in the HLA region and can now potentially link HPV type and host genotype for a prediction of disease outcome. Again, the kinds of technology available could only be wished for here; so too the registry and survey options.

Molecular and General Virology contributed talks parallel session

I attended this because of my continued fascination with veterinary and plant viruses – and because Anna-Lise was covering the Clinical and Molecular session – and was not disappointed: talks were of a very high standard, and the postgraduate students especially all gave very good accounts of themselves.

Melanie Platz (Univ Koblenz-Landau, Germany) kicked off with a description of a fascinating interface between mathematics and virology for early warning, spatial awareness and other applications. She gave an example using a visual representation of risk using GIS for Chikungunya virus, based on South African humidity and temperature data going back nearly 100 years: this had a 3D plot model, into which one could plug data to get predictions of mosquito likelihood. They could generate risk maps from the data, to both inform public and policy / planning. They had a GUI for mobile devices for public information, including estimates of risk and what to do about it, including routes of escape.

This was followed by one of my co-supervised PhD students, Aderito Monjane – who recently got the cover of Journal of Virology with his paper on modelling maize streak virus (MSV) movement and evolution, so I will not detail more here. However, even as a co-supervisor I was blown away by the fact that he was able to show animations of MSV spread – at 30 km/yr, across the whole of sub-Saharan Africa.

Christine Rey of Wits University provided another state-of-the-art geminivirus talk, with an account of the use of siRNAs and derivatives for silencing cassava-infecting geminiviruses. They were using genomic miRNA precursors as templates to make artificial miRNAs containing viral sequences, meaning they got no interference with nuclear processing and there was less chance of recombination with other viruses, a high target specificity, and the transgenes would not be direct targets of virus-coded suppressors. They could also use multiple miRNAs to avoid mutational escape. The concept was successful in tobacco, and they had got transformation going well for cassava, so hopes were high for success there.

Dionne Shepherd (UCT) spoke on our laboratory’s 15+ year work on engineered resistance in maize to MSV. She pointed out that the virus threatens the livelihood of 200 million+ subsistence farmers in Africa, and is thought to be the biggest disease concern in maize – which is still the biggest edible crop in Africa. Most of the work has been described elsewhere with another journal cover; however, new siRNA-based constructs still under investigation were even more effective than the previous dominant negative mutant-based protection: the latter gave 50-fold reduction in virus replication, but silencing allowed > 200-fold suppression of replication.

Arvind Varsani – a former UCT vaccinology PhD who is now a structural biology and virology lecturer at Univ Christchurch (NZ) – described what is probably the first 3D structure of a virus to come out of Africa. This was of a 30 nm isometric ssRNA virus – Heterocapsa circularisquama RNA virus (HcRNAV) – infecting a dinoflagellate, which is one of the most noxious red tide bloom agents and is a major factor in killing farmed oysters. The virus apparently controls the diatom populations. There are two distinct strains of virus, and specificity of infection is due to the entry process, as biolistic bombardment obviates the block. The single capsid protein probably has the classic jelly-roll β-barrel fold, but they observe a new packing arrangement that is only distantly related to the other ssRNA (+) virus capsids known. They will go on to look at structural differences between strains that change cell entry properties.

FF Maree from the Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute and the Univ Pretoria spoke on structural design of FMDV to improve vaccine strains: they wished to engineer viruses by inserting the cell culture adapted HSPG-binding signature sequence and to mutate capsid residues to increase the heat stability of SAT-2 subtype virus vaccines. If they put the signature sequence in a SAT1 virus, they found it could infect CHO cells – which do not express any of 4 integrins that FMDV binds to, but are far better for large-scale production of the virus than the BHK cells used till now. It was also possible to increase hydrophobic interactions in the capsid by modeling: eg a VP2 Ser to Tyr replacement gave a considerably better thermal inactivation profile to the virus.

Daria Rutkowska (Univ Pretoria) detailed how African horsesickness orbivirus (AHSV) VP7 protein had significant potential as a scaffold that could act as a vaccine carrier. The native protein formed as trimers assembled in a VP3+VP7 “core” particle; however, the VP7 when expressed alone could form soluble trimmers – and the “top” domain hydrophilic loop can tolerate large inserts. The group had very promising FMDV P1 peptide responses from engineered VP7 constructs, including protection of experimental animals.

P Jansen van Veeren of the National Institute of Communicable Disease in Johannesburg finished off the session, with a description of the cellular pathology caused by Rift Valley fever bunyavirus (RVFV) in mice in acute infections. The virus seems to have been of particular international interest recently as a potential bioterror agent; however, global warming is also responsible for its mosquito vector spreading outside of its natural base in Africa to the Arabian peninsula, and there are fears of the virus getting into Europe soon. While there are vaccines against the virus, including a live attenuated version, none are licenced for human use. It was interesting to hear that the viral NP appears to be the main immunogen, as there are massive amounts of NP produced in infection, and huge responses to it in infected animals – and NP immunisation protects mice. There is a good Ab response but it is not neutralising, while NP is released independently of other proteins from infected cells. The liver is the major target of virus infection, with a bias to apoptosis of hepatocytes and severe inflammatory responses. Viral load is linked to these effects and is much lower in vaccinees. Immunisation reduces liver replication markedly; that in the spleen less so. A screen of cytokines and other gene responses showed a big down-regulation of many genes in non-vaccinated mice to do with cytokines, and down-regulation of B and T cells and NK cells. He thinks recombinant vaccine candidates should have both the surface glycoproteins and the NP in order to be effective – and that there is a major need for proper reagents for big animal studies.