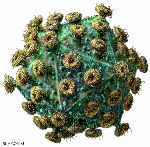

HIV: a retrovirus. Courtesy of http://www.rkm.com.au

The Wednesday morning agenda for the conference followed a somewhat bemusing Tuesday evening entertainment: one day I will learn NOT to involve myself in anything that involves getting onto a fleet of buses in the company of several hundred other people, and especially not in Bangkok! It took us one-and-a-half HOURS to go from the venue to the Navy Yard for a reception and supper – but the first half an hour was spent just going around the block, such is the traffic density at rush hour. There followed the standard fare for a conference in any country with any sort of culture: local entertainment (drummers and folk running around with bolts of cloth in this case), together with so-so food with very little choice, too much noise, and no possibility of being heard more than one person away. But thankfully, only a twenty minute ride back!

“New Prevention Strategies” was the theme for the second set of plenaries – which were opened (unexpectedly; she was second on the programme, but No 1 overslept) by our very own Carolyn WIlliamson (IIDMM, UCT), speaking on implications for combination prevention strategies from HIV pre- and post-infection studies. Carolyn noted again a point first raised by Pontiano Kaleebu on the first evening, that future vaccine efficacy trials should as as a matter of ethics offer preventions – eg ARVs – as a minimum standard of care, which will affect size and expense as well as endpoints like acquisition and disease progress.

She pointed out that 80% of infections with HIV were due to single viruses – but 20% were due to multiple infections, influenced by dose, IV injection, MSM transmission, inflammatory genital tract infections and the like. The lesson from study of the Phambili and STEP trial breakthrough infections by sieve analysis showed vaccination had had a selective effect on T-cell pressure. Phambili got 277 sequences from 43 people, in vaccine and placebo arms. The Merck vaccine had no effect on the transmission bottleneck. Scanning sites across the genome showed 2 sites of selection in Gag and 1 site in Nef were significantly different in the two arms; one in the region p6 of Gag looks like an epitope escape. There was a weaker signal in Phambili than in STEP, however: this was due in part to the lower number of participants (the trial was stopped before recruitment was complete), the fact that there were men and women involved vs mainly men in STEP, among other factors.

It is worth remembering that the Phambili and STEP trials were stopped in 2007, and reported on at a very gloomy AIDS Vaccine Conference in Cape Town (covered here in ViroBlogy).

There was also no effect of pre-exposure Tenofovir on the transmission bottleneck, or evidence of immunity in highly exposed uninfected individuals using the gel – despite the evidence for “chemovaccination” in macaques, due to abortive infection checked by ARVs in target cells. Thus, chemovaccination did not enhance the of impact microbicides and preinfection immune responses would not interfere with vaccine monitoring by this assay.

Tenofovir did impact early Ifn-g Gag-specific CD4+ responses post infection – indicating that possibly the drug prevents the initial destruction of CD4 cells in the gut, which would be a very valuable result.

Carolyn finished by noting that the implication for combination of preventive therapies is that it will increase the complexity of trials, make them cost considerably more, and make them longer. However, microbicides that reduce inflammation may dramatically reduce infections, ARVs may increase the barrier to infections, and also increase the time for the effects of vaccination to kick in and increase post infection immunity, and combination of multiple partially effective interventions may have significantly greater impact than any alone.

Helen Weiss (London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygeine) was the late riser: she spoke on lessons from male circumcision for other prevention strategies. It was interesting to many of us that it was a study in Nairobi in 1989 that showed the effect first – circumcision protected to some extent against in infection even in the presence of genitourinary diseases (GUDs). A metastudy combining 15 studies subsequently showed reduced risk in all, to a 60% protection level. Accordingly, three studies had been set up in Uganda, Kenya and SA in 2005-2007 to directly study the effect. They saw 50% efficacy in all locations, and all were stopped early as there was an obvious effect, with all participants being offered circumcision. The studies saw an overall 58% protective effect, and the effect in the Uganda trial persists up to 5 years post trial.

As for why this should be, Helen said that some studies say that the inner foreskin has a greater density of Langerhans and T-cells compared to the outer – and there is some evidence the inner is more easily infected in explant studies. HIV infections also induce retention of Langerhans cells within the epidermis of the inner foreskin. There is evidence that the inner foreskin facilitates efficient entry and translocation of cell-associated HIV, retention of Langerhans cells, and the incidence of infection is greater in men with larger foreskin area.

The conclusion was that one should offer circumcision in HIV prevention studies where heterosexual contact is the mode of transmission. Among MSM, habitual penile inserters show some effect of protection, while habitual accepters are obviously not protected.

She closed by commenting that scaling up circumcision to 80 % coverage of adults and newborns by 2014 could save US$ 40 billion US: however, the reality was that uptake was slower than planned, with only 2.6% done by 2010. However, there was obvious buy-in with a fourfold increase in circumcisions between 2009-2010.

While I thought she oversold the intervention rather – it is decidedly less simple than drug or microbicide interventions after all, benefits only one partner directly, and the lesson in South Africa is that even communities with a high circumcision rate can have very high prevalences of HIV infection – there is no doubt that circumcision in combination with pre- and post-exposure ARVs and microbicides cannot do other than have an additive effect in protection, and possibly even a synergistic one in some cases.

For me that was the morning; I missed three very worthy parallel late morning oral sessions while dealing with nagging emails – but started fresh again in the post-lunch period (an aside: best conference coffee break munchies and light lunches I have ever seen…B-), with Oral Session 11 – Mucosal Immunity.

Anthony Smith introduced us to a fascinating study of transcriptional “imprints” correlating with protective immunity in macaques following vaccination with the live attenuated SIV-∆-Nef virus, done by microarrays on RNAs from the cervix. Smith noted that live attenuated viruses offer some of the best protection available in monkeys, and that SIV Mac239-∆-Nef was one of the best. They isolated total RNA ex the cervix of rhesus macaques post-challenge with a heterologous virus at 140 days with native virus and tested unvaccinated and vaccinated samples with an Affymetrix rhesus chip. There was 103-fold less viral RNA in vaccinated animals, and very little overlap of gene expression – only 1% (eg 5 genes) – of 405 vs 246 unvaccinated to vaccinated samples. There was greater expression of inhibitors of innate immunity and inflammation in vaccinees; MIP3alpha expression was higher in unvaccinated monkeys – this brings in effector cells, including CD4+ T-cells, which would enhance infection. Unvaccinated monkeys get a signalling cascade of cytokines which cause an inflammatory response – vaccinees get a short circuit in this signalling by mucosal conditioning with mutant virus. There were important differences in humoral responses too, which were not reported here. In light of this one could almost wish that the proposed trial in humans in the 1990s of the natural Nef deletant HIV-1 found in Sydney and associated with long-term non-progression had gone ahead – but only almost, as people with the virus did eventually start to progress to AIDS.

Steve Reeves then spoke on mucosal natural killer (NK) cells in SIV infected monkeys in chronic infection: he noted that NK cells respond early in infection in a variety of tissues. They act to suppress viral replication in vitro, and are linked to disease control in vivo. while much of what he said was straight over my head – I really do not have much truck with cytokine signalling cascades and lymphoid cell types and subtypes – it is becoming increasingly evident that not only are NK cells actively involved in controlling HIV infections, but that there are hitherto unsuspected variations among them, and often evidence of specificity in their interaction with infected cells. Expect to hear much more about these fascinating guys in the future….

There followed a slightly disappointing talk by Shari Gordon, on the use of Human papillomavirus (HPV) pseudovirions (PsV), made in cell culture from co-expression of transfected HPV L1 and L2 capsid proteins and a replicating plasmid vaccine, to immunise mice vaginally. The idea was to use a mucosa-infecting agent to make a vaccine which induces T-cells and antibody responses at mucosal sites to prevent HIV infection, during the window of opportunity where founder infections are being established. HPV naturally infects the disrupted vaginal mucosa via interactions of L1 and L2 with receptors on basal keratinocytes – thus it was necessary to disrupt the vaginal epithelium by administration of progesterone and the known inflammatory agent nonoxynol-9 in order to infect. They used HPV-16 PsV vectoring a SIV gag gene, then boosted with non-cross-reacting HPV-45 PsVs, both expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) as a marker for in vivo fluorescence tracking.

They got a good response to HPV, and see anti-Gag IgA in vaginal secretions and IgG in serum. They also see recruitment of T-cells to the site of infection in mucosa – both CD4 and 8 and activated cells. T-cell responses assayed by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) showed that they get CD4+ and 8+ cells in tissue and in blood, which waned over time. They then set up an experiment to see if systemic priming and mucosal HPV PsV boosting could protect macaques, using a regime consisting of sequential HPV-16, -45 and -58 PsV administration, with and without ALVAC + gag, and gp120 administered with the PsV 45 and 58. They saw the same gp120 titres at the end of the regimen, with or without ALVAC priming. They got a Gag-specific response, which expands and recruits T-cells in the genital tract but was lower in blood. The response was better with ALVAC priming. There was a primarily monospecific response of both CD4 and 8 T-cells, and primary effector memory. Upon SIV challenge they saw a similar rate of acquisition despite the immune responses – however, they were only in mid-experiment, and still hoped to see viral control. She noted the vaccine does not exacerbate the SIV infection rate.

While this was all good science, it was disappointing for a number of reasons. First, they did not do or report the obvious control, of using DNA only in parallel with PsVs. Second – in the opinion of my resident HIV/HPV vaccine expert, Anna-Lise Williamson – such vaginal immunisation using PsVs in humans would be a complete non-starter, because it is not ethically acceptable to use agents like nonoxynol-9, which is known to increase HIV infection rates, in a vaccine regimen. Third, the vaccine did not seem to be very good, despite the supposed advantage of using particles to deliver a DNA vaccine: this is a subject close to my heart, given an interest in both HPV VLPs and DNA vaccines, and I think that oral or intranasal immunisation would have been a far better idea. Fourth, and although this was not stated, the PsVs are made in immortalised 393TT cells expressing significant amounts of an oncogenic viral protein (polyomavirus T antigen) to enable replication of the vector plasmid – all of which I am sure would be a stern no-no for use in humans.

H Li spoke on the use of recombinant adenovirus vectors in monkeys: he noted that effector memory cells were induced by replicating viruses while non-replicating induced primarily memory cells in blood. However, people had not looked at mucosal responses. Accordingly, they used single or double recombinant Ad26 immunisations and showed one could get mucosal T-cells. With a heterologous Ad5/26 prime/boost they get a potent and widely distributed T-cell response, which they have followed for 4 yrs and still see the responses 2.5 yrs post boost. Mucosal T-lymphocytes are persistently activated. They looked at T-cells in PBMC vs colon, duodenum and vaginal tissue: the latter were activated while PBMC were not, so there was only transient activation here. Memory phenotype shows Tem (effector memory) to Tcm (core memory) evolution in the periphery. Mucosal T-cells show a persistent Tem1 phenotype.

Ming Zeng revisited the attenuated live SIV vaccine, and its mucosal protective properties. Live attenuated vaccines offer the best protection yet in monkeys against homologous or heterologous virus challenge – and understanding the correlates would help understand design principles for human vaccines.

They inoculated monkeys with SIV-∆-Nef intravenously, and challenged with repeated intravaginal inoculation. He showed evidence of a fascinating vaccine-induced Ab concentration at the mucosal border of the monkey cervix, correlated with limited spread and prevention of infection. They cannot see significant challenge viral growth at portal of entry in vaccinees from 20 weeks post vaccination. Tissue-associated IgG is concentrated at the port of entry at 20 wk in the cervix and vagina: distribution of the IgG shows one gets plasma cells at the cervix, but also IgG-staining cells especially just underneath the epithelial cell layers. The cells are epithelial reserve cells and enrich IgG inside cells, presumably by uptake mediated by the neonatal IgG receptor expressed on their surfaces. This can be shown in vitro by incubating plasma cells with a filter-separated layer of epithelial cells from the female reproductive tract (FRT).

In challenge phase they noticed Ab concentration increased rapidly after challenge in situ. All genes involved in Ab synthesis were upregulated in challenged monkeys in FRT and germinal centre cells see a dramatic local expansion of plasmablasts after challenge – presumably of memory B cells.

They think the SIV-∆-Nef vaccine converts the FRT to an inductive site for B cell expansion and maturation. They get 5-10x the amount of IgG produced vs IgA. They think it is both local recruitment of B cells and activation of local cells that results in the IgG production – which is total and not just HIV-specific IgG.

Again, this is a fascinating result obtained using a controversial vaccine candidate – and one which is not going to go away.

Late afternoon Wednesday was the turn of Symposium Session 02: Recent Advances in B Cell & Protective Antibody Responses – and two talks that took the prize as far as I was concerned were one by Peter Kwong and the following one by Pascal Poignard, both from Scripps in San Diego.

I couldn’t pretend to do justice to the Kwong talk: the graphics were so good, and there was so much detail, that it was like watching a great big complicated shiny machine in motion. It was very beautiful, but I couldn’t tell you exactly what it is that he did. Suffice it to say that he introduced us to the concept of mining the “antibodyome” by using structural bioinformatics to get solutions for vaccines by deep sequencing. A consequence of this was that they could follow the maturation path of specific clones of cells making antibodies binding specific Env epitopes. An important thing to come out of his talk was a possible reason for why strongly-binding broadly-neutralising antibodies are so rare: they found that, for their preferred target of the CD4 binding site, initially-produced antibodies were of very low affinity and needed a lot of maturation to become strongly neutralising and broadly reactive – which, of course, meant the producing cells were generally selected against and did not make it to being memory B-cells. Knowing what was possible, however, and being able to make antigens to stimulate those antibodies specifically, would make for a rational vaccine design strategy.

Pascal Poignard described something that has been much in the news lately: the recent discovery of many strongly-binding broadly-neutralising monoclonal antibodies in people living with HIV. He detailed how the IAVI protocol G search screened 1800 donors, mainly from Africa, for “elite neutralisers”. They took the top four and did high throughput screening of memory B cells with antigen, and rescued the Ab gene sequences from selected wells, triaged them, and ended up with a selection of potent neutralising MAbs. These were mostly broadly neutralising, but some were very potent – tenfold better than the previous best. One group of 5 MAbs – all from the same individual – bind at various sites around the V1 and 2 and 3 loops of Env; another group of 3 from different individuals bind glycans and the V3 loop. Data suggest protection needs 100x the IC50 value – which was very low for most of them, meaning they could be highly efficacious at low concentration, and synergise each other’s effective in mixtures. Certain combinations of MAbs would give better protective coverage than others – especially if they did not neutralise the same spectrum of viruses.

The work raises all sorts of very interesting possibilities, including mimicking the structures bound so well by these MAbs in order to elicit them more frequently, as well as using them therapeutically or in prevention regimes. As far as antibodies are concerned, it is apparent that we are in a new era of sophistication as regards the potential for both exploiting the natural “antibodyome”, and even designing our own.

There followed a most enjoyable “Faculty Dinner” – my wife got me invited – on the 54th floor of the Centara Grand Hotel, followed by an even more enjoyable sojourn with pleasing beverages on the open deck of the 55th floor, overlooking Bangkok.

Until it rained, anyway.