The following text has now appeared in modified form in an ebook, for sale for US$4.99 on the iBooks Store

A Short History of the Discovery of Viruses

While people were aware of diseases of both humans and animals now known to be caused by viruses many hundreds of years ago, the concept of a virus as a distinct entity dates back only to the very late 1800s. Although the term had been used for many years previously to describe disease agents, the word “virus” comes from a Latin word simply meaning “slimy fluid”.

Porcelain filters and the discovery of viruses

The invention that allowed viruses to be discovered at all was the Chamberland-Pasteur filter. This was developed in 1884 in Paris by Charles Chamberland, who worked with Louis Pasteur. It consisted of unglazed porcelain “candles”, with pore sizes of 0.1 – 1 micron (100 – 1000 nm), which could be used to completely remove all bacteria or other cells known at the time from a liquid suspension. Though this simple invention essentially enabled the establishment of a whole new science – virology – the continued development of the discipline required a string of technical developments, which I will highlight as appropriate.

Pasteur Germ Proof Filter, c. 1890, Pasteur-Chamberland Filter Co., Dayton, Ohio – Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago)

As the first in what was to be an interesting succession of events, Adolf Eduard Mayer from Germany, publishing in 1886 on work done in Holland from 1879, showed that the “mosaic disease” of tobacco – or “mozaïkziekte”, as he named it in his paper – could be transmitted to other plants by rubbing a liquid extract, filtered through paper, from an infected plant onto the leaves of a healthy plant. However, he came to the erroneous conclusion that it must be a bacterial disease.

The first use of porcelain filters to characterize what we now know to be a virus was reported by Dmitri Ivanovski in St Petersburg in Russia, in 1892. He had used a filter candle on an infectious extract of tobacco plants with mosaic disease, and shown that it remained infectious: however, he concluded the agent was probably a toxin as it appeared to be soluble.

The Dutch scientist Martinus Beijerinck in 1898 reported similar experiments with bacteria-free filtered extracts, but made the conceptual leap and described the agent of mosaic disease of tobacco as a “contagium vivum fluidum”, or contagious living fluid, because he was convinced the infectious agent had a liquid nature. The extract was completely sterile, could be kept for years, but remained infectious. The term virus was later used to describe such fluids, also called “filterable agents”, which were thought to contain no particles. The virus causing mosaic disease is now known as Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV). A paper commemorating Ivanovsky and Beijerinck’s work – “One Hundred Years of Virology” – was published in Journal of Virology 1992 to honour both pioneers.

The first animal viruses

The second virus discovered was what is now known as Foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) of farm and other animals, in 1898 by the German scientists Friedrich Loeffler and Paul Frosch. Again, their “sterile” filtered liquid proved infectious in calves, providing the first proof of viruses infecting animals – a fact commemorated by an article in 1998 in the Journal of General Virology. Indeed, some believe that the true discoverers of viruses were these two scientists, as they concluded the infectious agent was a tiny particle, and was not a liquid agent. The two went further by showing that it was possible to vaccinate cows and sheep against the disease using filtered vesicle extract that had been heated sufficiently to destroy its infectivity: this was possibly the first use of an inactivated virus as a prophylactic vaccine.

In 1898 G Sanarelli, working in Uruguay, described the smallpox virus relative and tumour-causing myxoma virus of rabbits as a virus – but on the basis of sterilisation by centrifugation rather than by filtration.

The first human virus: yellow fever

The first human virus described was the agent which causes yellow fever: this probably originated in Africa, but was spread along with its mosquito vector Aedes aegyptii to the Americas and neighbouring islands by the slave trade. Indeed, the declaration of independence from France by Haiti in 1804 was made possible in part by the devastating effect of the disease on the French army sent to quell a slave revolt there. The virus was discovered and reported in 1901 by the US Army physician Walter Reed, after pioneering work in Cuba by Carlos Finlay reported in 1881 hypothesising that mosquitoes transmitted the deadly disease.

The agent became the subject of intense study because, in the Spanish-American war in Cuba in the 1890s, about 13 times as many soldiers died of yellow fever as died from wounds. The subsequent eradication of mosquitoes in Panama is probably what allowed the completion of the Panama Canal – stalled because of the death rate among workers from yellow fever and malaria.

Rinderpest and rabies

The paper describing rinderpest as a virus disease

A finding that was later to have great importance in veterinary virology was the discovery by Maurice Nicolle and Adil Mustafa (also known as Adil-Bey), in Turkey in 1902, that rinderpest or cattle plague was caused by a virus. This had been for several centuries the worst animal disease known worldwide in terms of mortality: for example, an epizootic or animal epidemic in Africa in the 1890s that had started in what is now Ethiopia in 1887 from cattle imported from Asia, had spread throughout the continent by 1897, and killed 80-90% of the cattle and a large proportion of susceptible wild animals in southern Africa. Many thousands of people died of starvation as a result. The virus is, incidentally, only the second to have ever been eradicated – nearly 100 years after its discovery.

Viruses and Vaccines

Sir Arnold Theiler, a Swiss-born veterinarian working in South Africa, had been appointed as state veterinarian for the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek prior to 1899, on the strength of his having produced a smallpox vaccine for miners in the Johannesburg area. He then developed a crude vaccine against rinderpest by 1897, without knowledge of the nature of the agent: this consisted of blood from an infected animal, injected with serum from one that had recovered – something also shown to work with FMDV by Loeffler and Frosch. This risky mixture worked well enough, however, to eradicate the disease in the region. He went on to do the same thing successfully for African horsesickness virus and other disease agents, in an institute (Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute) that still works on the virus.

The description in Annales de l’Institut Pasteur by Remlinger and Riffat-Bay in 1903 of the agent of rabies as a “filterable virus was the culmination of many years of distinguished work in France on the virus, started by Louis Pasteur himself. While Remlinger credited Pasteur with having the notion in 1881 that rabies virus was an ultramicroscopic particle, the fact is that Pasteur and Emile Roux had also, in 1885, effectively made a vaccine against rabies by use of dried infected rabbit spinal cords, without any knowledge of what the agent was.

Title page of the original article in Annales de l’Institut Pasteur Volume 17 of 1903

It is interesting that the same volume of the Annales which reported the rabies agent also has a discussion on whether or not the smallpox agent variola virus and the vaccine against it, vaccinia virus, were differently-adapted variants of the same thing, or were different viruses.

More and more viruses

The viral nature of many disease agents started to be made evident around this time, as more researchers started investigating known diseases. In 1904, E Baur in Germany described an infectious variegation of Abutilon that could only be transmitted by grafting, that was not associated with visible bacteria. This is now known to be due to Abutilon mosaic virus, now known to be a single-stranded DNA geminivirus.

Abutilon mosaic

Incidentally, the earliest recorded description of a plant disease was probably in a poem in 752 CE by the Japanese Empress Koken, describing symptoms in eupatorium plants. It was shown in 2003 that the striking yellow-vein symptoms were caused by a geminivirus infection.

Interestingly, also in 1906, A Zimmermann proposed – in a paper entitled “Die Krauselkrankheit des Maniok” – that the agent of mosaic disease of cassava that had first been described from German East Africa (now Tanzania) in 1894, was a filterable virus. This was the second geminivirus discovered, although this was only proved in the 1970s.

Cassava affected by a recombinant African cassava mosaic virus in western Kenya, 1997. Insets, from left: healthy cassava, mild disease, severe disease

In 1906, Adelchi Negri – who had previously discovered the Negri bodies in cells infected with rabies virus – showed that vaccinia virus, the vaccine for the dreaded smallpox caused by variola virus, was filterable. This was the final step in a long series of discoveries around smallpox, that started with Edward Jenner’s use of what was supposedly cowpox, but may have been horsepox virus to protect people from the disease in 1796.

An Egyptian stele thought to represent a polio victim (1403–1365 BC). Note the characteristic withering of one leg.

The disease now known as poliomyelitis was first clinically described in England in 1789, as “a debility of the lower extremities”. However, it had been known since ancient times, and had even been depicted clearly in an Egyptian painting from over 3000 years ago.

An important development in human virology in 1908, therefore, was the finding by Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper in Germany that poliomyelitis or infantile paralysis in humans as it was known then, was caused by a virus: they proved this by injecting a cell-free extract of a suspension of spinal cord from a child who had died of the disease, into monkeys, and showing that they developed symptoms of the disease.

Viruses and cancer

In 1908, Oluf Bang and Vilhelm Ellerman in Denmark were the first to associate a virus with leukaemia: they successfully used a cell-free filtrate from chickens with avian leukosis to transmit the disease to healthy chickens.

The first solid tumour-causing virus, or virus associated with cancer, was found by Peyton Rous in the USA in 1911. He showed that chicken sarcomas, or solid connective tissue tumours, could be transmitted by grafting, but also that a filterable or cell-free agent extracted from a sarcoma was infectious. The virus was named for him as Rous sarcoma virus, and is now known to be a “retrovirus”,as is chicken leukaemia virus,in the same virus family as HIV.

Eaters of Bacteria: The Phages

Two independent investigations led to the important discovery of viruses that infect bacteria. In 1915, Frederick Twort in the UK accidentally found a filterable agent that caused the bacteria he was growing to lyse, or burst open. Although he showed that it could pass through porcelain filters, and could be transmitted to other colonies of the same bacteria, he was not sure whether or not it was a virus, and referred to it as “the bacteriolytic agent”. It is interesting that he was actually attempting to grow vaccinia virus in culture, and that it was a contaminating staphylococcus that he noticed was being lysed by his infectious agent.

The original article published by Twort in The Lancet in 1915

Subsequently, Félix d’Hérelle in Paris published in 1917 that he had discovered a virus that lysed a bacterial agent he was culturing in liquid broth – a Shigella – that caused human dysentery, or diarrhoea. He named the virus “bacteriophage”, or eater of bacteria, derived from the Greek term “phagein”, meaning to eat. He showed a number of interesting properties of his shigella-specific bacteriophages, including that they could be adapted to other Shigella species or types by passaging them repeatedly, and that they protected rabbits against infection by lethal doses of bacteria.

D’Hérelle’s main interest in his new discovery was in using them as a therapeutic agent for bacterial infections in humans: sadly, this idea did not take off in Europe or the Americas, largely due to the unreliability of the ill-understood phage preparations, although it was extensively exploited in the former USSR. Indeed, he mentored George Eliava who went on to found the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, which became a major centre for the use of bacteriophage cocktails against persistent bacterial infections in humans. A review on phage therapy from the Institute was recently published to mark the centenary of Twort’s discovery in 1915. An excellent – if slightly childish – animation describing phages and phage therapy can be seen here.

D‘Hérelle’s main interest in his new discovery was in using them as a therapeutic agent for bacterial infections in humans: sadly, this idea did not take off in Europe or the Americas, although it was extensively exploited in the former USSR.

The 1896 paper from Annales de l’Institut Pasteur

Interestingly, and as reported in ViroBlogy previously, what could have been the first discovery of phages was probably described by Ernest Hankin, who had previously proved in India that cholera was caused by bacteria. In 1896 in Annales de l’Institut Pasteur, he documented that river water downstream of cholera-infested towns on the Jumma river in India contained no viable Cholera vibrio – and that this was a reliable property of the water, and was probably responsible for limiting the spread of cholera.

While he did not prove the presence of a “filterable agent”, he was recognised by d’Hérelle and others as having contributed to the discovery of bacteriophages. In fact, d’Hérelle went to India in 1927, and put cholera phage preparations into wells in villages with cholera patients: apparently the death toll went down from 60% to 8%.

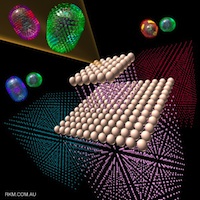

Influenza A viruses in waterbirds – Russell Kightley Media

The virus as human plague: the Spanish Flu

Possibly the worst human plague the world has ever seen swept across the planet between 1918 and 1922: this was known as the Spanish Flu, from where it was first properly reported, and it went on to kill more than 50 million people all over the world. We now know it to have been H1N1 influenza type A: modern reconstruction of the virus from archived tissue samples and frozen bodies found in permafrost has shown it probably jumped directly into humans from birds.

Most medical authorities at the time thought the disease was caused by bacteria – however, MJ Dujarric de la Rivière, and Charles Nicolle – brother of Maurice – and Charles Lebailly in France, separately proposed in 1918 that the causative agent was a virus, based on properties of infectious extracts from diseased patients. Specifically, they found that the infectious agent derived from bronchial expectoration of an infected person was filterable, caused disease in monkeys via nasal administration and human volunteers via subcutaneous injection, and was not present in the blood of an infected monkey. However, many scientists at the time still doubted that influenza was a viral disease – despite this contemporary comment in the British Medical Journal of 1918.

Conclusions from the Nicolle and Lebailly paper

Translation of this passage (courtesy of Mrs Francoise Williamson):

“Conclusions.

1⁰ The bronchial expectoration of people suffering from flu, collected during the acute period, is virulent.

2⁰ The monkey (M. cynomolgus) is sensitive to the virus by sub-conjunctival and nasal inoculation.

3⁰ The flu agent is a filterable organism. The inoculation of the filtrate has indeed reproduced the illness in two of the people injected subcutaneously; on the other hand when given intravenously it appears to be ineffective. (two failures out of two tries).

4⁰ It is possible that the influenza virus does not occur in the patient’s blood. The blood of a monkey with influenza, inoculated subcutaneously, did not infect man; the negative blood result of subject 2 at D, is however, not convincing, the blood route seeming to be ineffective for the flu virus transmission.”

Other agents of other diseases were found to be “filterable viruses” in the 1920s, including yellow fever virus by Adrian Stokes in 1927, in Ghana. Indeed, the US bacteriologist and virologist Thomas Rivers in 1926 counted some sixty-five disease agents that had been identified as viruses.

Virus Assays: Counting the Viruses in the 1920s

The discovery of bacteriophages was a landmark in the history of virology, as it meant that for the first time it was relatively easy to work with viruses: many kinds of bacteria could be grown in solid or liquid culture quite easily, and the life cycle of the viruses could be studied in detail. In fact, this later led to the birth of molecular biology, as described here.

However, the beauty of working with phages was that they could be assayed – or counted in terms of infectious units – so easily, either by the plaque technique or by infections of liquid cultures. This was not true of viruses of plants or of animals in the absence of similar culture techniques; these could only be assayed in a much more crude method using whole organisms. One such method was by determining infection endpoints by serial dilution of inoculum, such as the now-famous ID50, or dose infecting 50% of the experimental subjects.

This changed in 1929 for plant viruses, with the demonstration by the plant virus pioneer FO Holmes that local lesions caused by infection of particular types of tobacco by TMV could be used as a means of assaying the infectivity of virus stocks. This was then extended to other virus/host combinations, and allowed the rapid and quantitative assay of virus stocks – which, as it had done for phages, allowed the study of the properties of plant viruses, and led to their biological isolation and then purification.

TMV-induced local lesions in N. tabacum cv. glutinosa

Eggs and animals for virus culture

Chicken eggs for virus growth and assay

Possibly the next most important methodological development in virology after the discovery of phages was the proof that embryonated or fertilized hen’s eggs could be used to culture a variety of important animal and human viruses. Ernest Goodpasture, working at Vanderbilt University in the USA, showed in 1931 that it was possible to grow fowlpox virus – a relative of smallpox – by inoculating the chorioallantoic membrane of eggs, and incubating them further.

While tissue culture had in fact been practiced for some time – for example, as early as the 1900s, investigators had grown “vaccine virus” or the smallpox vaccine now called vaccinia virus in minced up chicken embryos suspended in chicken serum – this technique represented a far cheaper and much more “scalable” technique for growing pox- and other suitable viruses.

An important first in a chain of related discoveries was the one by Howard Andervost, at Harvard University in 1929, who showed that human herpes simplex virus could be cultured by injection into the brains of live mice.

This led to the demonstration in 1930 by the South African-born Max Theiler – son of Sir Arnold – also at Harvard, that yellow fever virus could be similarly cultured: this allowed much easier handling of the virus, which until then had to be injected into monkeys in order to multiply it in their livers. In addition, it allowed the development of attenuated or weakened strains of virus, by him and in parallel by a French laboratory, by serial passage or repeated transmission of the virus between mice. He also incidentally caught yellow fever from one of his mice through a laboratory accident. Culturing in mouse brains also allowed the successful animal testing of vaccine candidates, and of protective antisera, for which Theiler was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1951.

Until 2008, this was the first and only recognition of virus vaccine work by the Nobel Foundation.

A consequence of this work was the landmark in medical virology that was the development of human vaccines against yellow fever virus, by Wilbur Sawyer in the USA in 1931: this followed on Theiler’s mouse work in using brain-cultured virus plus human immune serum from recovered patients to immunize humans – very similar to Theiler Senior’s strategy with rinderpest, more than thirty years later.

here for Part 2: The Ultracentrifuge, Eggs and Flu

here for Part 3: Phages, Cell Culture and Polio

and here for Part 4: RNA Genomes and Modern Virology

Copyright Edward P Rybicki and Russell Kightley, February 2012, except where otherwise noted.