This was originally written as an Answer to a Question posted to Scientific American Online; however, as what they published was considerably shorter and simpler than what I wrote, I shall post the [now updated] original here.

The answer to this question is not simple, because, while viruses all share the characteristics of being obligate intracellular parasites which use host cell machinery to make their components which then self-assemble to make particles which contain their genomes, they most definitely do not have a single origin, and indeed their origins may be spread out over a considerable period of geological and evolutionary time.

Viruses infect all types of cellular organisms, from Bacteria through Archaea to Eukarya; from E. coli to mushrooms; from amoebae to human beings – and virus particles may even be the single most abundant and varied organisms on the planet, given their abundance in all the waters of all the seas of planet Earth. Given this diversity and abundance, and the propensity of viruses to swap and share successful modules between very different lineages and to pick up bits of genome from their hosts, it is very difficult to speculate sensibly on their deep origins – but I shall outline some of the probable evolutionary scenarios.

The graphic depicts a possible scenario for the evolution of viruses: “wild” genetic elements could have escaped, or even been the agents for transfer of genetic information between, both RNA-containing and DNA-containing “protocells”, to provide the precursors of retroelements and of RNA and DNA viruses. Later escapes from Bacteria, Archaea and their progeny Eukarya would complete the virus zoo.

It is generally accepted that many viruses have their origins as “escapees” from cells; rogue bits of nucleic acid that have taken the autonomy already characteristic of certain cellular genome components to a new level. Simple RNA viruses are a good example of these: their genetic structure is far too simple for them to be degenerate cells; indeed, many resemble renegade messenger RNAs in their simplicity.

RdRp cassettes and virus evolution

RNA virus supergroups and RdRp and CP cassettes

What they have in common is a strategy which involves use of a virus-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or replicase to replicate RNA genomes – a process which does not occur in cells, although most eukaryotes so far investigated do have RdRp-like enzymes involved in regulation of gene expression and resistance to viruses. The surmise is that in some instances, an RdRp-encoding element could have became autonomous – or independent of DNA – by encoding its own replicase, and then acquired structural protein-encoding sequences by recombination, to become wholly autonomous and potentially infectious.

A useful example is the viruses sometimes referred to as the “Picornavirus-like” and “Sindbis virus-like” supergroups of ssRNA+ viruses, respectively. These two sets of viruses can be neatly divided into two groups according to their RdRp affinities, which determine how they replicate. However, they can also be divided according to their capsid protein affinities, which is where it is obvious that the phenomenon the late Rob Goldbach termed “cassette evolution” has occurred: some viruses that are relatively closely related in terms of RdRp and other non-structural protein sequences have completely different capsid proteins and particle morphologies, due to acquisition by the same RdRp module of different structural protein modules.

Given the very significant diversity in these sorts of viruses, it is quite possible that this has happened a number of times in the evolution of cellular organisms on this planet – and that some single-stranded RNA viruses like bacterial RNA viruses or bacteriophages and some plant viruses (like Tobacco mosaic virus, TMV) may be very ancient indeed.

However, other ssRNA viruses – such as the negative sense mononegaviruses, Order Mononegavirales, which includes the families Bornaviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Filoviridae and Paramyxoviridae, represented by Borna disease virus, rabies virus, Zaire Ebola virus, and measles and mumps viruses respectively – may be evolutionarily much younger. In this latter case, the viruses all have the same basic genome with genes in the same order and helical nucleocapsids within differently-shaped enveloped particles.

Their host ranges also indicate that they originated in insects: the ones with more than one phylum of host either infect vertebrates and insects or plants and insects, while some infect insects only, or only vertebrates – indicating an evolutionary origin in insects, and a subsequent evolutionary divergence in them and in their feeding targets.

HIV: a retrovirus

The Retroid Cycle

The ssRNA retroviruses – like HIV – are another good example of possible cell-derived viruses, as many of these have a very similar genetic structure to elements which appear to be integral parts of cell genomes – termed retrotransposons – and share the peculiar property of replicating their genomes via a pathway which goes from single-stranded RNA through double-stranded DNA (reverse transcription) and back again, and yet have become infectious. They can go full circle, incidentally, by permanently becoming part of the cell genome by insertion into germ-line cells – so that they are then inherited as “endogenous retroviruses“, which can be used as evolutionary markers for species divergence.

The Retroid Cycle

Indeed, there is a whole extended family of reverse-transcribing mobile genetic elements in organisms ranging from bacteria all the way through to plants, insects and vertebrates, indicating a very ancient evolutionary origin indeed – and which includes two completely different groups of double-standed DNA viruses, the vertebrate-infecting hepadnaviruses or hepatitis B virus-like group, and the plant-infecting badna- and caulimoviruses.

Metaviruses and pseudoviruses

These are two families of long terminal repeat-containing (LTR) retrotransposons, with different genetic organisations.

Members of family Pseudoviridae, also known as Ty1/copia elements, have polygenic genomes of 5-9 kb ssRNA which encode a retrovirus-like Gag-type protein, and a polyprotein with protease (PR), integrase (IN) and reverse transcriptase / RNAse H (RT) domains, in that order. While some members also encode an env-like ORF, the 30-40 nm particles that are an essential replication intermediate have no envelope or Env protein. They are not infectious. Host species include yeasts, insects, plants and algae.

Metaviruses – family Metaviridae – are also known as Ty3-gypsy elements, and have ssRNA genomes of 4-10 kb in length. They replicate via particles 45-100 nm in diameter composed of Gag-type protein, and some species have envelopes and associated Env proteins. Gene order in the genomes is Gag-PR-RT-IN-(Env), as for retroviruses. One virus – Drosophila melanogaster Gypsy virus – is infectious; however, as for pseudoviruses, most are not. The genomes have been found in all lineages of eukaryotes so far studied in sufficient detail.

Both pseudovirus and metavirus genomes are clearly related to classic retroviruses; moreover, RT sequences point to metavirus RTs being most closely related to plant DNA pararetrovirus lineage of caulimoviruses. This gives rise to the speculation that pseudoviruses and metaviruses have a common and ancient ancestor – and that two different metavirus lineages gave rise to retroviruses and caulimoviruses respectively.

All of these cellular elements and viruses have in common a “reverse transcriptase” or RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, which may in fact be an evolutionary link back to the postulated “RNA world” at the dawn of evolutionary history, when the only extant genomes were composed of RNA, and probably double-stranded RNA. Thus, a part of what could be a very primitive machinery indeed has survived into very different nucleic acid lineages, some viral and many wholly cellular in nature, from bacteria through to higher eukaryotes.

The possibility that certain non-retro RNA viruses can actually insert bits of themselves by obscure mechanisms into host cell genomes – and afford them protection against future infection – complicates the issue rather, by reversing the canonical flow of genetic material. This may have been happening over aeons of evolutionary time, and to have involved hosts and viruses as diverse as plants (integrated poty– and geminivirus sequences), honeybees (integrated Israeli bee paralysis virus) – and the recent discovery of “…integrated filovirus-like elements in the genomes of bats, rodents, shrews, tenrecs and marsupials…” which, in the case of mammals, transcribed fragments “…homologous to a fragment of the filovirus genome whose expression is known to interfere with the assembly of Ebolavirus”.

Rolling circle replication

There are also obvious similarities in mode of replication between a family of elements which include bacterial plasmids, bacterial single-strand DNA viruses, and viruses of eukaryotes which include geminiviruses and nanoviruses of plants, parvoviruses of insects and vertebrates, and circoviruses and anelloviruses of vertebrates.

Geminivirus particle

These agents all share a “rolling circle” DNA replication mechanism, with replication-associated proteins and DNA sequence motifs that appear similar enough to be evolutionarily related – and again demonstrate a continuum from the cell-associated and cell-dependent plasmids through to the completely autonomous agents such as relatively simple but ancient bacterial and eukaryote viruses.

Big DNA viruses

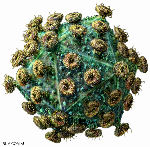

Mimivirus particle, showing basic structure

However, there are a significant number of viruses with large DNA genomes for which an origin as cell-derived subcomponents is not as obvious. In fact, one of the largest viruses yet discovered – mimivirus, with a genome size of greater than 1 million base pairs of DNA – have genomes which are larger and more complex than those of obligately parasitic bacteria such as Mycoplasma genitalium (around 0.5 million), despite their sharing the life habits of tiny viruses like canine parvovirus (0.005 million, or 5000 bases).

Mimivirus has been joined, since its discovery in 2003, by Megavirus (2011; 1.2 Mbp) and now Pandoravirus (2013; 1.9 -2.5 Mbp).

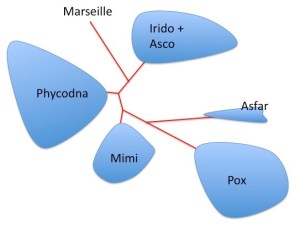

The nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses or NCLDVs – including pox-, irido-, asfar-, phyco-, mimi-, mega- and pandoraviruses, among others – have been grouped as the proposed Order Megavirales, and it is proposed that they evolved, and started to diverge, before the evolutionary separation of eukaryotes into their present groupings.

It is a striking fact that the largest viral DNA genomes so far characterised seem to infect primitive eukaryotes such as amoebae and simple marine algae – and they and other large DNA viruses like pox- and herpesviruses seem to be related to cellular DNA sequences only at a level close to the base of the “tree of life”.

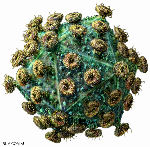

Variola virus, the agent of smallpox. Image courtesy Russell Kightley Media.

This indicates a very ancient origin or set of origins for these viruses, which may conceivably have been as obligately parasitic cellular lifeforms which then made the final adaptation to the “virus lifestyle”.

However, their actual origin could be in an even more complex interaction with early cellular lifeforms, given that viruses may well be responsible for very significant episodes of evolutionary change in cellular life, all the way from the origin of eukaryotes through to the much more recent evolution of placental mammals. In fact, there is informed speculation as to the possibility of viruses having significantly influenced the evolution of eukaryotes as a cognate group of organisms, including the possibility that a large DNA virus may have been the first cellular nucleus.

In summary, viruses are as much a concept as a unitary entity: all viruses have in common, given their polyphyletic origins, is a base-level strategy for replicating their genomes. Otherwise, their origins are possibly as varied as their genomes, and may remain forever obscure.

I am indebted to Russell Kightley for use of his excellent virus images.

Updated 12th August 2015

About half the world’s oxygen is being produced by tiny photosynthesising creatures called phytoplankton in the major oceans. These organisms are also responsible for removing carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and locking it away in their bodies, which sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die, removing it forever and limiting global warming.

About half the world’s oxygen is being produced by tiny photosynthesising creatures called phytoplankton in the major oceans. These organisms are also responsible for removing carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and locking it away in their bodies, which sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die, removing it forever and limiting global warming.