Plant-Based Vaccines, Antibodies and Biologics: the 5th Conference

Verona, Italy, June 2013

The return of this biennial meeting to Verona – the third time it has been held here – was a welcome change; while the previous meeting in Porto in 2011 may have been good, the city was nothing like as pleasant a place to relax. My group is now familiar enough with Verona that we know just where to go to get pasta by the riverside – or, on this occasion, “colt loin with braised onion and potatoes” and “stewed horse with red wine”. Which seem more palatable, somehow, as “Costata di puledro con cipolle brasate e patate” and “Stracotto di cavallo speziata” respectively, but were enjoyed anyway.

The conference kicked off with an opening plenary session, chaired by the Local Organizing Chair, Mario Pezzotti, of the University of Verona. The headline act was a talk on taliglucerase alfa – aka glucocerebrocidase, a Gaucher Disease therapeutic – by Einat Almon of Protalix Therapeutics from Carmiel, Israel. I featured the product here last year, after an earlier feature here; suffice it to say that it has soared since FDA approval, and now Protalix is pushing hard with new plant-made products to follow it up. While they use carrot cells for taliglucerase alfa, apparently they are using suspension-cultured tobacco cells for other products – and are using an easily-scalable disposable 800 litre plastic bag system, with air-driven mixing of cells suspended in very simple, completely mammal-derived product free media. Hundreds of patients had been treated with the drug for up to 5 years with no ill effects, and the possibility of switching therapies from mammalian cell-made products to the plant cell-made had been successfully demonstrated.

Scott Deeter of Ventria Biosciences (Ft Collins, USA) spoke next, on “Commercializing plant-based therapeutics and bioreagents”. His company has possibly the most pragmatic attitude to the production and sale of these substances that I have yet met, and he struck a number of chords with our thinking on the subject – which of course, post-dates theirs! Ventria use self-pollinating transgenic cereals for production of seed containing the protein of interest, and rice in particular, for safety reasons – and because the processing of the seeds is very well understood, and the purification processes and schedules are common to many food products and so do not require new technology. He reckoned that a company starting out in the business needed an approved product in order to give customers confidence – but should also engage in contract services and contract manufacture of client-driven products in order to avoid being a one-product shop. To this end, they had received APHIS Biological Quality Manufacturing Systems (BQMS) certification (similar to ISO9001), with the help of the US Biotechnology Regulatory Services.

Their therapeutic products included diarrhoea, ulcerative colitis and osteoporosis therapeutics which were already in phase II clinical trial. Scott noted that in particular, recombinant lactoferrin was a novel product, which could only feasibly be produced in the volumes and at the price required for effective therapy, by recombinant plant-based production systems. It also filled a high unmet need as a therapy for antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in the US, with +/-3 million patients at risk annually who presently cost service providers over $1500 each for treatment.

A third commercialization option was bioreagents and industrial enzymes, which they marketed via a vehicle called InVitria: they had a number of products already in the market, which Scott claimed gave confidence to the market and to partners, while building capacity to make therapeutics. Something that was particularly attractive to our prospects was that a collection or pool of small volume products – say $5-10 million each – gave a respectable portfolio. He noted that Sigma Aldrich and Merck were already marketing their human serum albumin, which competed effectively with serum- and yeast-derived products.

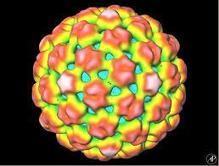

George Lomonossoff from the John Innes Centre in Norwich, UK, spoke next on “Transient expression for the rapid production of virus-like particles in plants” – a subject close to our hearts, seeing as we have for the last five years been associated with George and partners in the Framework 7-funded PlaProVa consortium. He mentioned as an object example the recent success in both production and an efficacy trial of complete Bluetongue virus (BTV) serotype 8 VLPs, made in Nicotiana benthamiana via transient expression using their proprietary Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) RNA2-derived pEAQ vector: this was published recently in Plant Biotechnology Journal.

Another very useful technology was the use of CPMV capsids as engineered nanoparticles: one can make empty VLPs of CPMV at high yield by co-expressing the coat protein (CP) precursor VP60 and the viral 24K protease: the particles are structurally very similar to virions in having a 0.85 nm pore at 5-fold rotational axes of symmetry, meaning they can be loaded with (for example) Co ions. It is also possible to fuse targeting sequences – such as the familiar RGD loop – into the surface loops of the CPMV CPs, and to modify the inner surface too. One application would be to engineer Cys residues exposed on the inside, which could bind Fe2+ ions: this would result in particles which could be targeted to cancer cells by specific sequences, then heated using magnetic fields.

John Butler of Bayer Innovation GmbH (Leverkusen, Germany) closed out the session with an account of lessons learned from the development of the plant-derived non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) vaccine, that they had acquired with Icon Genetics, who in turn had inherited it from the sadly defunct Large Scale Biology Corp. It was rather depressing to hear that Bayer had dumped the vaccine, despite the developers having reached their targets in turning 43 of 45 tumour samples into lifetime individualized supplies of vaccine within12 weeks, and despite the phase I trial being as successful as could be hoped. To this end, the vaccines had been well tolerated and were immunogenic; of the patients who reacted immunologically, all but one were still tumour-free presently.

He felt that the problem was that NHL trials were too long and therefore too expensive as it was a slow-progressing disease; that a different clinical approach was needed, and that using the vaccines as a first-line therapy instead of only after the 2nd or 3rd relapse would be a much better idea. The main lesson learned was that proving the technology would be far better done with a therapeutic vaccine for a fast-acting cancer, which would allow 1-2 year clinical trials with overall survival as an endpoint.

(more coming)